When Glidden S. Doman passed away June 6, 2016, at the age of 95, the world lost the last of the pioneers of the original six U.S. helicopter companies. Doman, of Granby, Connecticut, was a renowned aeronautical engineer, and through his company Doman Helicopters Inc., he played a significant role establishing the U.S. helicopter industry alongside industry legends Igor Sikorsky (Sikorsky Aircraft), Arthur Young (Bell Aircraft), Stanley Hiller (United Helicopters — later Hiller Helicopters), Charles Kaman (Kaman Aircraft), and Frank Piasecki (Piasecki Helicopter Corp.).

Doman was born on Jan. 28, 1921 in Syracuse, New York, and grew up in nearby Elbridge, gaining his first exposure to rotary-wing flight through a ride in a Pitcairn autogiro when he was about 12 years old.

After graduating from the University of Michigan in 1942, he found work with Ranger Aircraft Engine, a division of Fairchild Aviation in Farmingdale, New York. Doman’s interest in rotary-wing technology was piqued after the publicity of Sikorsky’s early flight of the VS-300 helicopter, and he attended Society of Automotive Engineers meetings in New York where Sikorsky spoke on helicopter development.

Doman had gained experience in strain gauge technology while at Ranger, and could see that the vibration stresses in helicopter rotors was an area that needed attention. In 1943, Doman approached Sikorsky about a job possibility, and was hired. His work at Sikorsky was deemed so important, he was not drafted into the U.S. military during World War II.

At the time, Sikorsky YR-4 helicopters were coming off the production line, but they were having problems with rotor blade fractures. The fatigue life of a blade was only about 40 hours.

Doman placed strain gauges on the blades and the rotor hub, and soon discovered major stresses in the fabric-covered blades and hub. He accompanied a Sikorsky production test pilot on an R-4 strain gauge flight evaluation. After flying at different speeds Doman had the pilot slow the helicopter down to 20 miles per hour (32 kilometers per hour). The R-4’s engine immediately quit and for a time the helicopter was uncontrollable. The pilot was only able to gain cyclic control after increasing the speed to about 30 m.p.h. (48 km/h) and flying backwards. Doman adjusted the three blades, and the result allowed the aircraft to fly smoothly with low control. Sikorsky personnel were enthralled, and Doman was put in charge of matching and balancing the rotor blades of the R-4s prior to delivery.

Moving out on his own

He continued to gain valuable experience in rotor dynamics while at Sikorsky, but left in the fall of 1945 to form a new company that would develop a new and better hingeless rotorhead. He was originally accompanied by Clint Frazier, a friend and mathematician from Sikorsky, and the two established Doman-Frazier Helicopters, Inc. in New York in 1946.

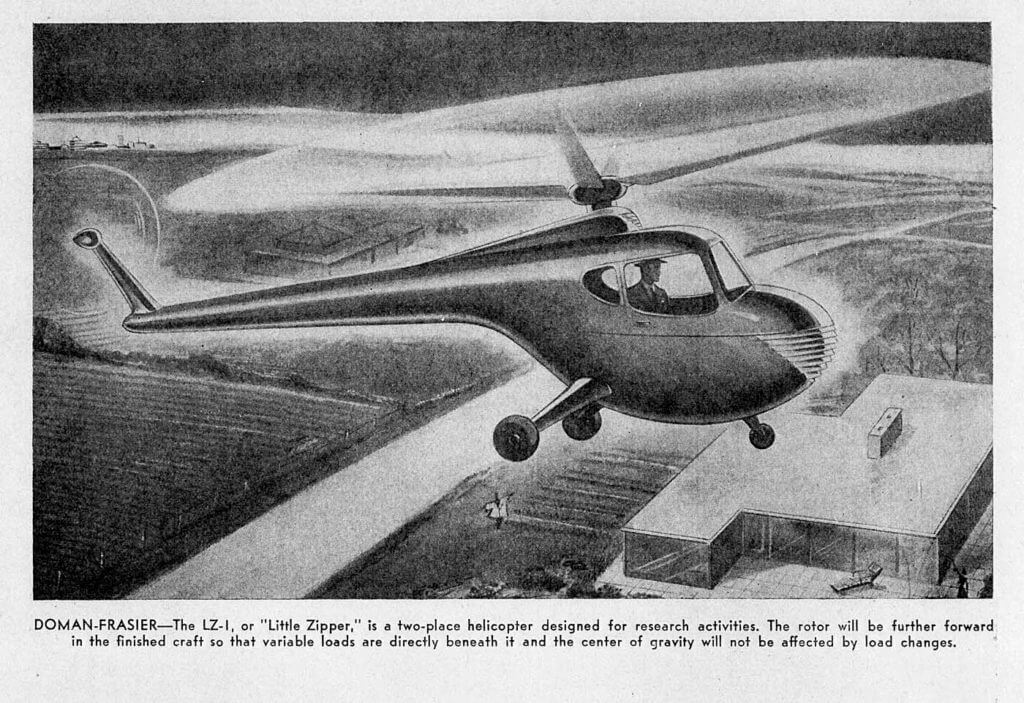

Doman managed to obtain a war-surplus Sikorsky R-6 to test his new hingeless gimbaled self-lubricating rotorhead with four blades, and raised $30,000 to convert it. Engineering test pilot Robert Nields flew the R-6/LZ-2 “Little Zipper” in August 1946 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The rotor system was a complete success, resulting in much smoother flight. Doman provided the flight test data to the military at Wright Field for free, and the following year he was given a flight test research contract from the now U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Field.

With Frazier’s departure and a move to Danbury, Connecticut, in 1948, the company name changed to Doman Helicopters, Inc. Alan Bott, an ex U.S. Navy helicopter pilot and an engineering class friend of Doman’s, joined the company as a test pilot.

Construction of the first Doman ship — the LZ-3 — began in January 1949. Further market evaluation led to the LZ-3 going from 250 to 400 horsepower, and its rotor blades being lengthened from 45 feet to 48 feet. As a result, the helicopter was given a new number: the LZ-4. It was an experimental prototype designed and hand-built in only 10 months.

The Curtiss-Wright Corp. approached Doman about a joint venture and licensing of the LZ-4, which was called the CW-40 by Curtiss-Wright. The eight-place LZ-4/CW-40 first flew in 1950, piquing the interest of the U.S. Army. The Army had the chance to fly the aircraft, and were interested in purchasing several production versions. Curtiss-Wright had no interest in dealing with the Army, and moved the LZ-4/CW-40 to Caldwell, New Jersey, after terminating the agreement with Doman.

The Doman LZ-5

Design features of the LZ-4 were incorporated into Doman’s LZ-5 — a general-purpose utility helicopter capable of carrying eight passengers. The supercharged Lycoming 580-D 400-horsepower engine was located beneath the pilot’s compartment. Engine cooling was accomplished by a Doman-developed exhaust ejector system, and the engine was coupled to the rotor transmission by a fluid starting clutch.

The unique Doman gimbal-mounted rotor system allowed the rotors to retain dynamic balance in all flight attitudes with minimum vibration. All moving parts were contained within a common housing and no blade flapping hinges, drag hinges, or hinge dampers were required. The Doman rotor was always in balance. This same mechanical feature was incorporated in the tail rotor.

The rotor blades were made from plastic bonded birchwood laminates with an armor sheath of solid nylon over the leading edge. The rotor diameter was 48 feet (14.63 meters).

The fuselage was composed of tubular construction with a metal skin, and contained a large main cabin for passengers and cargo with doors on both sides. A compartment in the back carried additional baggage.

The helicopter’s length was 38 feet (11.58 meters), and it had a gross weight of 5,200 pounds (2,359 kilograms), an empty weight of 2,860 lb. (1,297 kg), and a useful load of 1,950 lb. (884 kg).

The LZ-5’s cruising speed was 86 m.p.h. (138 km/h), its maximum speed was 105 m.p.h. (169 km/h), its range was 245 miles (394 kilometers), and it had an absolute ceiling of 18,000 feet (5,486 meters).

A quadricycle wheeled undercarriage provided high stability for landing in rough terrain.

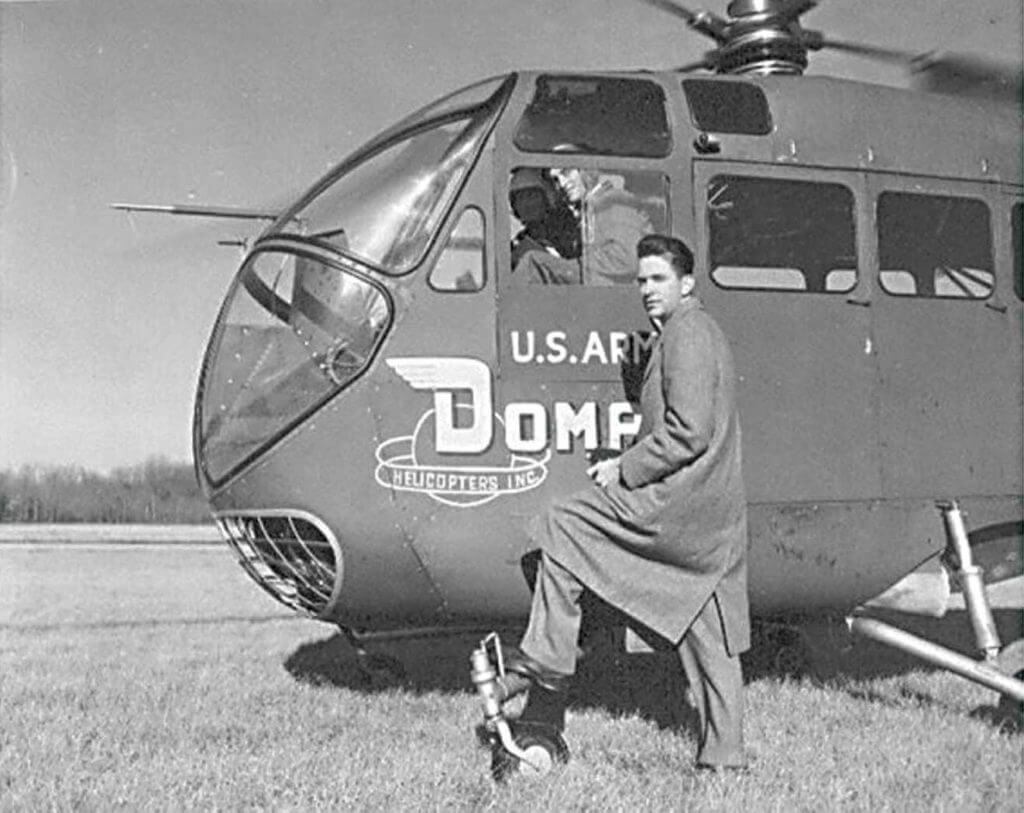

In 1952, the military signed a contract for two LZ-5s (designated the YH-31 by the military). The first flight, performed by test pilot Turpen Girrard, took place on April 27, 1953, and was deemed a success. By the end of the year, Doman delivered two aircraft to Fort Rucker, Alabama, for test and evaluation. Despite interest in the aircraft from both the Army and the Air Force, no additional orders for the military LZ-5 were forthcoming, and the two YH-31s were used for passenger transportation in Washington until the Army disposed of them in 1958.

In 1954 Doman and Fleet Manufacturing Ltd. in Fort Erie, Ontario, formed a jointly-owned subsidiary — Doman-Fleet Helicopters Ltd. — to build the LZ-5 in Canada. One LZ-5 was produced the following year, flown by pilot Denis Bryan on June 4. It was the second helicopter to be designed and built in Canada after the post-war Sznycer SG-Vl.

The LZ-5 received Civil Aeronautics Authority certification in the U.S. in 1955, and a Canadian certificate of airworthiness in 1956. Over the next two years, the helicopter was demonstrated in Ontario and Quebec to the military and commercially, but there was little interest in it. The helicopter was returned to Doman in 1957, and continued to fly on commercial demonstrations — including at the Paris Air Show in 1960. Doman later upgraded it with instrumentation for blind flight training and demonstrated it as a helicopter trainer.

Doman’s efforts to obtain financial assistance to get into commercial production seemed to be bearing little fruit. He traveled to Puerto Rico, Italy, and France with the LZ-5 in search of financial support, but no production agreements ever came to be.

The Twin Coach Aircraft Division Company in Buffalo, New York, worked with Doman on a proposal for an upgraded LZ-8 for the Army XH-40 turbine helicopter, but nothing came of it.

Moving onto new pastures

As he struggled to get his LZ-5 into production, Doman set his sights on new helicopter programs. The helicopter industry was rapidly changing as new larger turbine helicopters entered the market, and Doman looked at new models such as the D-10B with a Lycoming 0-720 engine, and later with a turbine engine. The Doman Model D-10C was a 10-place stretched version, evolved from the LZ-5. A Pratt & Whitney PT-6 turbine-engined D-10C variant was another option.

Over the years, Doman submitted proposals for the U.S. Navy antisubmarine competition, the USAF rescue helicopter competition, the Light Observation Helicopter turbine joint competition with Kaiser Fleetwings and Doman (KD-161), and a Canadian Navy antisubmarine helicopter competition among others. None of the submissions were successful.

By December 1969, Doman Helicopters was finished. Being unable to secure financial backing, Doman was forced to close its doors after 24 years of pioneering helicopter development. William Gallagher from Winchester, Connecticut, purchased the company’s assets, including its patents.

Today, two helicopters survive from the company’s work — a Sikorsky R-6 with a Doman rotorhead and a Doman LZ-5. Both are on display at the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Connecticut.

Following his company’s closure, Doman joined Boeing Vertol’s helicopter research department. While there, he helped design rotors for heavy-lift helicopters. Doman got involved in wind energy research in the early 1970s, beginning a second career. His experience in helicopter rotor dynamics was used in the new wind turbine technology, where he designed two-bladed wind turbines with a teeter-hinge hub.

In 1978, Doman moved to Hamilton Standard, a division of United Technologies, where he continued his work on wind turbine technology. In 1987, Doman moved to Italy to oversee the company’s wind energy program. He formed a company in the 2000s (when he was in his 80s) to market the Gamma wind turbines that he had helped to design in Italy, and he remained active in wind turbine research and development right up to his death in 2016.

A select few have the distinction of reflecting on a career in which they’ve been a pioneer in an industry. Even fewer can claim to have done so in two industries. Having played such a key role in the early development of both helicopters and wind turbines, Glidden Doman will always be remembered as a remarkably talented figure among both communities.