Canada’s small but active helicopter aerial application industry is intimately tied to things that grow. And in a country where forestry and agriculture still make up a substantial part of the economy, the important role played by this small fleet of about 50 helicopters is greatly magnified.

Flying those rotary-wing ships are about a dozen operators, who regularly use their aircraft for spraying, dusting and fertilizing Canadian farms and forests. These 50 helicopters represent about 14 percent of Canada’s aerial application fleet of 350 fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft and just under three percent of Canada’s fleet of 1,820 active commercially registered helicopters.

While small in number, the work these machines do has far-reaching effects, such as helping increase crop yields and fighting bug infestations, maintaining pasture land and right-of-ways, accelerating forest regeneration, reducing frost damage, and controlling mosquitoes.

A New Perspective and Outlook

If the value and importance of this sector surprises you, you’re probably not alone. The first thing many people still think of when they hear the words aerial application is an image of the cavalier ag pilots or crop dusters of old.

But building a business on the well-timed and precise aerial delivery of herbicides, fungicides, fertilizers, pesticides, and biological bug-killing agents is not a job for helicopter pilots wanting to shirk responsibilities or take risks. It requires a skilled, professional workforce. (See Flying the Crops, p.74, Vertical June-July ’12)

The missions themselves are complex and present many challenges that require extensive training: aerial application helicopters fly fast and low, at maximum gross weight, and often in hot weather or high altitudes. The pilots must deliver chemicals extremely accurately within a spray block, in a landscape increasingly cluttered with unmarked obstacles and protected areas, and with valuable crops susceptible to improperly applied chemicals.

In terms of official oversight, the aerial application industry is subject to detailed and complex regulations and licensing. In Canada, this occurs on both a federal and provincial level, and requires strict compliance before an operator or a pilot can even begin to turn a rotor blade.

But for all its challenges, this is still a good time to be a part of the aerial application sector.

“The forecast for agriculture is very positive,” said Jill Lane, executive director of the Canadian Aerial Applicators Association (CAAA). “With global demand up and the price of commodities high, the agriculture community is using more professional services to assist them to care for their crops. Aerial application is one of those services, so the industry is definitely growing.”

In total, the CAAA estimates that aerial application aircraft treat between eight million and 10 million acres of agricultural land a year in Canada.

The Right Tools for the Job

To make sure those millions of acres are properly cared for, the aerial application sector uses a host of technology that presents a very unique contrast between the modern and the traditional.

On the modern side are GPS guidance and mapping systems that provide very precise information on the location of spray blocks, buffer zones and the lines to be flown. Most GPS guidance and mapping systems also use a visual lightbar mounted in front of the cockpit to guide pilots as they fly spray lines, so nothing is left to chance.

The traditional part of the equation lies in the aircraft themselves. Consider that Canada’s helicopter aerial application fleet includes Bell 47s, JetRangers and LongRangers; Eurocopter AStars; Aérospatiale Lamas; Hiller UH-12s; Hughes/Schweizer 269/300Cs; Robinson R44s; and an MD Helicopters MD 500E.

The most prolific helicopter model in service just happens to be the second-oldest design: the Hiller UH-12. In total, two operators have 13 Hillers in service — Western Aerial Applications flies eight and Bi-Air Application Services flies five (four of which are Soloy-Hiller UH-12ETs).

A somewhat newer design, the Robinson R44, has recently been gaining in popularity. There are currently 13 in service with five operators: Aerial Growth Management/Essential Helicopters, Apex Helicopters, Black Hawk Helicopters, Great Lakes Helicopter and Zimmer Air Services.

Due to the need for highly maneuverable, lost-cost aircraft that are mechanically easy to maintain, it’s likely that traditional models will continue their dominance for a while longer. But, as parts get more difficult to obtain on those older ships, the focus and cost benefit will likely shift to smaller, newer models.

Mosquito Control

One aspect of aerial applications that isn’t widely known is that it doesn’t just involve chemicals.

GDG Environnement, for instance, was founded in Trois-Rivières, Que., in 1980, just as the province was switching from insecticides to biological agents for mosquito control. Today GDG has more than 200 seasonal employees providing mosquito control within 60 municipalities in Québec and Ontario.

“We use a natural occurring bacterial agent [that is made into the larvacide] BTI (Bacillus thurigiensis israelensis) to target mosquito larva,” explained Richard Vadeboncoeur, a biologist and director of business development at GDG, who has also logged 10,000 hours as a fixed-wing spray pilot.

The company was not originally involved in the aviation side, but this changed in 1998 with the creation of GDG Aviation and the purchase of the company’s first fixed-wing aircraft. Its first helicopter followed just three years later.

Currently, GDG uses three airplanes (one Piper PA-25-260 Pawnee and two Cessna A188 “Ag Wagons”) to treat larger wetland areas. It uses its three Hughes/Schweizer 269/300C helicopters, meanwhile, to treat communities on the north side of the St. Lawrence River between Montreal and Trois-Rivières, and its Bell 206B JetRanger for contracts with mining towns in northeastern Québec.

“We start flying at eight or nine in the morning, since most of the areas where we fly are close to urban areas,” said Vadeboncoeur. “The granular BTI is not subject to as much drift as a liquid and is not susceptible to evaporation when being applied during warm temperatures, so we don’t need to start work at sunrise.

“The BTI is impregnated in pieces of corn in granular form that we drop using a Simplex blower system that produces a precise swath. The corn helps carry the BTI through the forest canopy to standing water and ponds where the mosquito larva are found.”

To carry out the mission, the pilots are well briefed and provided with digital maps that pinpoint the ponds, standing water and wetlands to be treated. Plus, all of GDG’s aircraft are equipped with Ag-Nav GPS guidance and tracking systems.

Said Vadeboncoeur: “The mosquito season in Québec runs from April to September and the number of aerial treatments is determined by how often it rains. We stop work after the first generation of mosquitoes and park all the equipment until it’s time to attack the next generation of larvae. Everything is timed according to when it rains.”

The Apple of Helico’s Eye

Another Québec aerial application specialist that focuses on the weather and precise, well-planned missions is Helico Service Inc.

Founded in 1983 by apple grower Benoit Tétreault, Helico started with a Bell 47G-4A and a focus on serving the local farming community in the Rougemont, Que., area, which is well known for its apple orchards.

“Apple orchards are not very large,” said Tétreault, “so a helicopter is ideal for precise spraying because of its lower speed — and the rotor downwash also helps provide coverage.”

Tétreault’s knowledge of his clients’ needs aided his company’s growth and success. A second Bell 47 was added to Helico’s fleet in 1990 and the first fixed-wing ship (a Piper PA-25-235 Pawnee) was brought on in 1994 to provide more capacity for larger fields.

Today, Helico operates one agricultural Bell 47G-4A, four Piper PA-25-235s, three Air Tractors (AT-402A, AT-502B and AT-504), and one Bellanca Citabria (for entry-level ag pilot training).

Helico’s Bell 47 operates within five miles of its Rougemont base, spraying fungicide on apples, grain and corn; and insecticide on sweet corn. During April and May, it is used for frost control, when apple trees are budding and blooming. “A drop in temperature can kill the apple buds,” said Tétreault. “We usually takeoff at first light and fly over the temperature inversion at about 100 to 150 feet and use the rotor to blow warm air down so it mixes with the colder air near the trees.”

The helicopter’s strength lies in smaller fields, especially those with a lot of obstacles. Plus, said Tétreault: “The Bell 47 is a rugged machine . . . . The Model 47G-4A has a more-powerful [Lycoming] VO-540 engine and a bigger 900 series transmission to handle the extra engine power. It’s not the highest-capacity aircraft, but if you use it correctly you will get very efficient results.”

Down on the Farm

Overall, the number of helicopters working in agriculture in Canada has approximately doubled since 2000 — partly because of newly introduced fungicides that can increase crop yields, and partly because strong commodity prices have meant farmers have the incentive and money to spend on aerial services.

“Commodity prices are high and farmers are willingly investing in aerial spraying to improve their yields,” said Chris Vankoughnett, president of Apex Helicopters in Wroxeter, Ont. (about 100 miles northwest of Toronto). “The introduction of new fungicides by chemical companies, such as BASF and Bayer, for crop protection have also helped stimulate a boom in aerial agricultural work across North America.”

Regionally, one of the areas of biggest growth has been in the corn, wheat and soybean fields of Southern Ontario and potato fields of Manitoba. One Ontario operator that is benefitting from this is Great Lakes Helicopter, who commenced operations in 2004 at the Region of Waterloo International Airport (about 65 miles southwest of Toronto).

“We operate two Robinson R44s for agricultural work and a JetRanger on forestry contracts,” said Stan Mance, a pilot and manager of spray operations for Great Lakes. “Since we started, there has been exponential growth in the number of acres receiving aerial fungicide applications in Ontario.”

Probably the strongest crop amidst the boom has been corn, which has skyrocketed in price and whose spraying cycle tends to favor aerial application.

Said Mance: “The best time to spray a fungicide on corn is when it is at the ‘tassel’ stage, when it is between six to 10 feet high, during a three-week period from late July to early August. Ground sprayers are not suitable to spray at this stage, because the corn is too high and driving through the fields will result in high crop loss.

“On a typical job, we’ll fly at 50 knots about four to eight feet above the crops and return to the mixing rig every three minutes. . . . . It’s a fun job and really dynamic, but you have to spend a lot of time pre-planning to know where the spray blocks and buffer zones are located.”

Apex Helicopters’ president Chris Vankoughnett recognized the opportunities to be had in the region while he was taking his helicopter flight training at Great Lakes. “I realized that there was a gap in the aerial application market in Southern Ontario and decided to start a helicopter company of my own dedicated to the aerial application business,” he remarked, adding, “The helicopter is ideally suited for herbicide application work in Southern Ontario, because the fields are smaller than in the United States and Western Canada, and there [are] lots of obstacles like powerlines, cell towers and wind turbines that make it difficult to use a fixed-wing aircraft.”

In addition to creating what he believes is the only dedicated agricultural aerial application operator in Ontario, Vankoughnett has also sought uniqueness in his equipment choice. “We selected the Robinson R44 for its low operating and acquisition cost. For the spray equipment, we selected the Apollo system made by Airwolf [Aerospace] in Ohio, which is about 20 pounds lighter than similar [competitive] systems.”

Finally, Vankoughnett also pursued innovation on the sales and marketing side: capitalizing on the rapid expansion of fungicide use, investing a lot of time attending farming events and teaming up with farming co-ops and agro-marts to bring up to 100 farmers together under a single spray contract.

Spray Is the Way

Another of Canada’s newer helicopter aerial application specialists is Westman Aerial Spraying in Brandon, Man. Although the company has actually been in the application business for almost 25 years, it only just got into rotary-wing operations a year-and-a-half ago.

“We probably spray about a quarter million acres of crops every year with our five Air Tractors [one AT-401, three AT-502s, one AT-802] and three high-clearance ground sprayers,” said president Jon Bagley.

Bagley said that 70 percent of the company’s work is taken up with spraying potatoes, while the rest is a combination of wheat, barley, oat, canola and soybean fields. “We bought a Robinson R44 with a Simplex system in late 2011 to meet the needs of our largest customer, who had some potato fields in confined areas we couldn’t spray with a fixed-wing aircraft.”

Potatoes are a particularly important crop for agricultural operators like Westman: they are sprayed 10 to 13 times a season at seven-day intervals to cover new leaf growth, which protects the plants from early and late blight (two diseases that can reduce crop yields).

Lesser-known, but equally important “crops” that rely on spraying are the commercial conifer forests in the provinces of New Brunswick, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia. Helicopters play an important role here in “conifer release” programs, which speed up regeneration of the commercial trees.

The goal of aerial application here is to eliminate the young deciduous trees and weeds that compete for sunlight and soil nutrients in a cut block replanted with coniferous trees. Use of herbicides “releases” the conifers to grow more rapidly.

The spray season lasts from late July to late September and occurs when the buds of the conifer trees have “waxed over” and the trees have become dormant, leaving deciduous plants open to air attack. This dormancy first occurs in northern regions, so spray programs begin in the northern forest blocks and then move south, creating a north-to-south migration of helicopters and support vehicles.

Bigger Can be Better

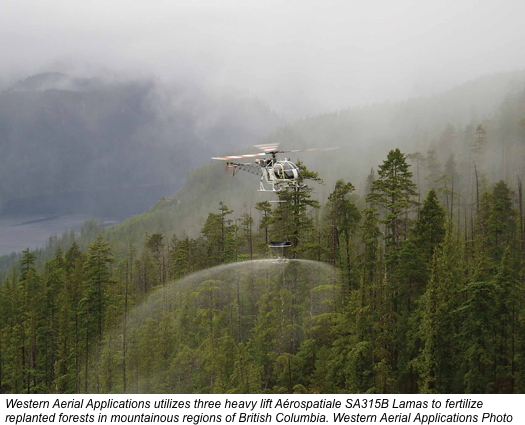

Based in Chilliwack, B.C. (about 60 miles east of Vancouver), with a fleet of 13 aircraft, Western Aerial Applications is Canada’s largest dedicated helicopter aerial applicator.

The company began life when the agricultural spray division of Conair Aviation was sold in the early 1980s to become CCA Crop Care Aviation and then later split into two companies, one of which (Abbotsford Spraying Services Ltd.) was helmed by Craig Murray and Jim Cooper and became Western Aerial.

“Today, the forestry sector makes up 90 percent of our work [herbicide application, fertilization] with public health flying [mosquito control] being second,” said Josh Jonker, operations manager.

The company credits its growth to specialization, innovation and safety.

Jonker said the company’s solution has been to “design, engineer and manufacture all of our own equipment, both for the air and the ground. Most of the time, we start from scratch and design equipment based on the experience we have gained from over 27 years of specialization.”

On the innovation side, Western Aerial was the first company in Canada to successfully deploy differential GPS parallel swath guidance on helicopters. This came from an early partnership with Trimble Navigation.

Its unique choice of helicopters has also been a component of the company’s success. Its 13-ship fleet currently encompasses one Bell JetRanger, three Aérospatiale SA315 Lamas, three piston-engined Hiller UH-12Es, five turbine-powered Soloy-Hiller UH-12ETs and a Cessna 180 flown for crew logistics and spare parts support.

“We find the Hiller has better capacity [than other light helicopters] and is more rugged and has better climb performance in the mountains,” said Jonker. “The Lamas were added for their extra capacity, incredible climb and descent capabilities, for fertilizing in the mountains, and excellent tail rotor authority . . . .”

As for safety, since the key often lies in the people, as well as the process, all of the company’s pilots are trained “from within”: they work as ground-support crewmembers first, learning the business and the company culture before beginning their flying career. Beyond helping create an excellent safety record, Jonker said this approach has also resulted in low pilot turnover and more focused flying skills.

The Way of the Rotor

Last, but certainly not least, in the cross-Canada aerial application tour is Bi-Air Application Services of Blackfoot, Alta. (near the Saskatchewan border). Bi-Air started as a fixed-wing agricultural operator in 1983, but has become primarily a helicopter operator specializing in forest-based aerial application.

“We started our business applying herbicides on farms in the Lloydminster area of eastern Alberta with fixed-wing aircraft,” said president Gordon Murray, “and then became a helicopter operator in 1999 after a couple of large helicopter operators left the aerial application market.”

Today, the company flies one Hiller UH-12E, four Soloy-Hiller UH-12ETs, an MD 500E and an Ayres S-2R-T Thrush. The switch to helicopters began when Bi-Air used a piston-powered Hiller UH-12E to spray community pastureland managed by the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration, taking over the work from fixed-wing aircraft.

Then, in 2001, Bi-Air fully changed its business focus when it won a long-term contract from Weyerhaeuser in Grande Prairie, Alta. This led to the eventual purchase of the first of four turbine-powered Soloy-Hiller UH-12ETs to spray herbicides, spread fertilizer and undertake aerial mapping work, as well as perform a range of odd jobs for other customers.

In 2012, Bi-Air bought Silver Helicopters of Prince George, B.C., and with it gained another long-term forestry contract, one that had been held for 21 years and that utilized an MD 500E Silver had acquired in 2003. The added benefit of the purchase is that Bi-Air can now have a longer operating season, moving its Soloy-Hillers to central British Columbia when its northern Alberta contracts are complete.

If the market sector’s continued innovation and growth is any indication, aerial application may soon become a much more widely recognized part of the helicopter industry.

Ken Swartz is an award-winning helicopter industry journalist who has covered the market for 35 years. He has spent most of his career as an international marketing and media relations manager with airlines and a leading commercial aircraft manufacturer. He runs Aeromedia Communications, a marketing and PR agency, and can be reached at kennethswartz@me.com.