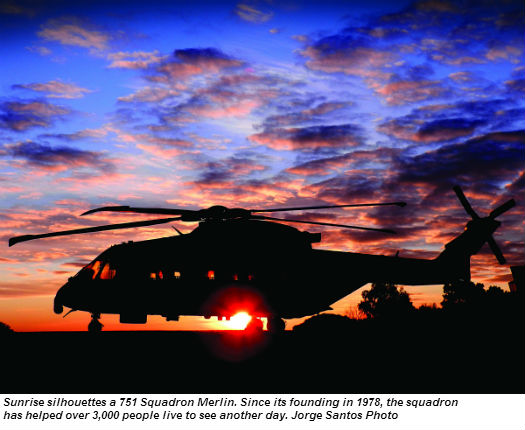

Editor’s note: Since this story was first published, Portugal’s 751 Squadron has surpassed 3,000 lives saved. Vertical congratulates the squadron on this impressive achievement.

Portugal is, by some measures, a small country. With a land area of around 35,500 square miles (91,900 square kilometers), it is about the same size as the state of Maine, and its population of 10.5 million is only slightly larger than that of New York City. But its strategic position on the North Atlantic — and more than 1,000 miles of coastline — has given it an outsized role in history, and the names of Portuguese explorers are still being taught to schoolchildren around the world.

More than 500 years after Vasco de Gama became the first European to sail directly to India, the Portuguese are still ranging far and wide over the Atlantic Ocean. Now, however, it’s in a search-and-rescue (SAR) capacity, and the ships have changed, too. Portugal provides coverage for the largest maritime SAR region in Europe, an area of roughly 2.3 million square miles that spans about a third of the North Atlantic. To do so, it relies heavily on the Portuguese Air Force’s 751 Squadron, which operates a fleet of AgustaWestland EH101 (now AW101) Merlin helicopters from three bases, including one in the Azores.

Making the most of the 101’s three engines and extended range capability, 751 Squadron performs ultra-longrange missions over the open ocean — often at night, in bad weather, with no options for an emergency landing. Round trips of 700 nautical miles are not uncommon, and the squadron has flown as far as 800 nautical miles on a single SAR mission without refueling. With no room for error, these exceptionally long-range missions demand the utmost from 751 Squadron’s aircraft and personnel. But the squadron has delivered on its motto of “para que outros vivam” — “so that others may live” — saving nearly 3,000 lives since its founding in 1978.

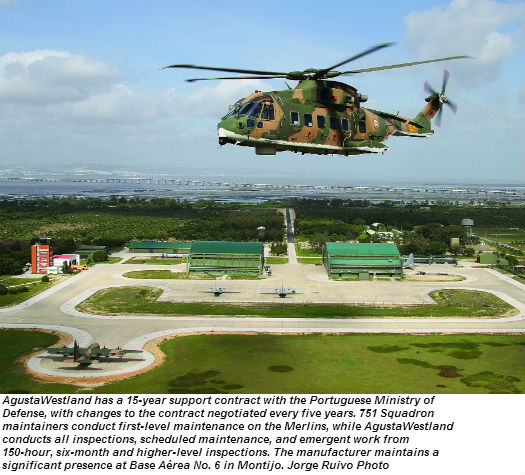

In September of last year, Vertical 911 met with 751 Squadron at its headquarters at Base Aérea No. 6 in Montijo, Portugal, riding along for a nighttime SAR training mission in the waters around Lisbon. There, we learned how the squadron’s pilots, flight crews, and maintainers work together with discipline and professionalism, “going the distance” in a way that few other SAR programs are asked to do.

Standing Ready

Portugal’s 751 Squadron is part of a national SAR system that integrates Air Force and Navy assets to provide comprehensive SAR coverage on land and at sea. The system includes two general rescue coordination centers and two maritime rescue coordination centers; there is one of each in Lisbon, the nation’s capital and largest city, and one of each in the Azores, the nine islands that form an autonomous region of Portugal approximately 1,000 miles west of the mainland. There is also a maritime rescue subcenter in Portugal’s other autonomous region, Madeira, an island archipelago west of Morocco and north of the Canary Islands. The system’s aviation assets are likewise well distributed: in addition to standing ready at its Montijo base near Lisbon, 751 Squadron maintains helicopters on SAR alert at Lajes, in the Azores; and at Porto Santo, in Madeira.

Today, 751 Squadron takes on a variety of missions as required, including aeromedical evacuations, VIP and tactical transport, and SIFICAP (fishing patrols; the acronym stands for “Sistema integrado de vigilância, fiscalização e control das actividades da pesca”). However, SAR remains its primary focus, as it has been since the squadron was founded more than 35 years ago. The squadron commenced operations with Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma helicopters, which it flew until acquiring its EH101 fleet in 2005 (and, indeed, for a short time afterward, due to issues with bringing the Merlins online). Although the Pumas served the squadron well — logging 30,000 flight hours and helping save 1,800 lives — the upgrade to the 101 brought with it a leap in capabilities. Perhaps the greatest improvement was the 101’s increased range, which nearly doubled the squadron’s radius of action. “We also gained a lot of space,” noted Rodolfo Gouveia, a 751 instructor pilot who began his career with the squadron in the Puma before transitioning to the 101. “We can bring more people, more equipment.”

There are 12 Merlins in the 751 Squadron fleet, replacing the 12 Pumas it operated previously. Six of these are in a basic SAR configuration, equipped for a standard five-person SAR crew that includes a winch/systems operator, a rescue swimmer, and a flight nurse, in addition to an aircraft commander and co-pilot. Another four aircraft are in a combat search-and-rescue (CSAR) configuration, with a tail and blades capable of folding for shipboard operations, as well as a missile approach warning system, radar warning receiver, chaff and flares dispenser, three general-purpose machine guns, and armor plating. With the exception of the folding blades and tail, SAR aircraft can be configured as CSAR aircraft, and CSAR aircraft can also be used for general SAR missions (although the squadron tries to avoid sending them to the Azores, as their extra weight makes them less suitable for ultra-long-range missions). The squadron also has two aircraft specifically configured for the SIFICAP role; these, too, can be used for SAR missions as required.

The squadron currently has 26 pilots, 16 rescue swimmers, and 15 winch/systems operators in its ranks, all of whom have received rigorous training for their in-flight roles (as have the nurses on SAR missions, although much of theirs takes place outside the military system). Pilot training in the Portuguese Air Force is similar to the United States Air Force system, with new pilots undergoing basic flight training (in Socata TB 30 Epsilon airplanes) before splitting off into fighter, transport, or helicopter tracks. Helicopter conversion training is done in the Sudaviation Alouette III, and new pilots typically have close to 300 total flight hours by the time they join 751 Squadron. From there, they follow a program of training and operational experience to achieve aircraft commander status, which, according to Gouveia, typically takes around two years.

Rescue swimmers are selected on the basis of competitive physical and psychological exams, then undergo a rigorous training course provided by the squadron. According to Paulo Candeias, a swimmer who has been with the squadron since 2006, the course generally takes around seven or eight months to complete, and involves training in a range of basic life-saving skills, followed by helicopter training in increasingly advanced maneuvers. “The worst mission we can do is when we’re going down to small ships in heavy seas,” Candeias said, noting that such missions require precision from everyone involved to avoid injury. “It’s a complicated situation at night. . . . If something happens to us, we can’t complete the mission.” (Here, the squadron benefits from the 101’s auto-hover capability, which has allowed it to complete difficult rescues it could not have attempted with the Puma.)

Meanwhile, winch operators are drawn from the ranks of maintenance supervisors, so they’re intimately familiar with the aircraft even before undergoing mission-specific training. Consequently, they’re available during SAR missions to advise the flight crew in a technical capacity — a form of backup that Gouveia said is particularly welcome on long over-water flights.

Altogether, there are around 30 aircraft maintainers in 751 Squadron; like the pilots and rescue swimmers, they alternate time at the Montijo base with shorter deployments in the Azores and Madeira. The squadron’s maintainers are responsible for first-level maintenance, and for clearing aircraft for flight. More advanced maintenance and inspection services are provided through AgustaWestland, which provides comprehensive operational support to the squadron through a Full In Service Support (FISS) agreement. AgustaWestland works closely with the squadron to maximize operational availability for the fleet, working with local talent and suppliers whenever possible. The manufacturer maintains an office at Base Aérea No. 6 in Montijo, where it has also made substantial investments in hangar improvements, spares, and information technology infrastructure.

“We are very much an integrated part of the squadron,” said Bill Hodson, general manager of AgustaWestland Portugal. “We want to get involved, we want to get results, and we’re increasing the reputation of the support capabilities that AgustaWestland can provide.”

When Every Minute Counts

Like many military organizations, the Portuguese Air Force has suffered budget cuts in recent years, forcing 751 Squadron to cut back on its flight hours (which are now down to around 1,750 hours per year). The squadron can’t turn down calls for help, but neither has it wanted to sacrifice on training, which is so critical to ensuring that high-stakes, time-critical rescue missions go off smoothly. Rather than reducing its training requirements, the squadron has been focusing on “getting more efficient” with training, said Gouveia. A good example of this was the nighttime SAR training mission that Vertical 911 witnessed, which involved hoisting exercises to ships and open water in the river and ocean around Lisbon. Three pilots and two swimmers took part in the mission, taking turns fulfilling their recency requirements over the course of a single, well-organized flight, rather than over multiple flights.

The squadron estimates that around half of its total flight hours are devoted to training exercises, and this practice pays off when it counts. On an ultra-long-range SAR mission, a crew will only have 30 minutes on station at an absolute maximum — which is not much time when conditions are difficult, as they often are. As Gouveia put it, “You need to be disciplined, fast, and you cannot make any mistakes out there.” That said, pulling off an 800-nautical-mile SAR mission owes as much to planning as execution. Flight crews study weather reports and forecasts carefully before their missions, and plan their cruise flight at altitudes that optimize fuel burn (they can also save around 440 pounds/200 kilograms of fuel per hour by shutting down the 101’s third engine during cruise). SAR missions with a radius of more than 120 nautical miles are typically supported by one of the Portuguese Air Force’s EADS C-295 airplanes, the crew of which can gather advance information for the helicopter crew to further aid in planning and preparation. In situations involving a medevac or rescue from a ship, the C-295 crew can also brief the ship’s captain on steps to take during the rescue operation.

This down-to-the-second planning can mean the difference between life and death, observed Paulo Candeias, who recalled one memorable rescue of a lone sailor on a boat in distress. Struggling on his own in rough conditions, the older man had been swept overboard, by which point he was so fatigued he failed to inflate his life vest. When Candelas reached him, he was face-down in the water, no longer breathing. “It was a matter of one minute more and he wouldn’t have been saved,” Candeias said.

That’s not the only rescue that sticks in Candeias’ mind, but there are too many to recount them all. The walls at 751 Squadron’s headquarters in Montijo are hung with used life vests and survival suits, and each one of them tells a different story: of a husband who would live to see his wife again, or a woman who would live to see her first grandchild. The common theme is that all of them were rescued by the crews and aircraft of 751. Asked what he likes best about his job, Candeias said it’s the looks on people’s faces when he arrives to rescue them.

“My favorite part is when someone is thinking they don’t have any possibility of being rescued, and then we arrive and take them from the water,” he said. It’s moments like these that define 751 Squadron and its purpose — para que outros vivam, “so that others may live.”