In the four short years since the first iPad was released, Apple’s signature tablet computer has become ubiquitous in the aviation industry. Countless aviation software applications have been developed for the iPad, the iPhone, and other smartphones and tablets: from simple weight-and-balance calculators, to full-featured flight planning apps like ForeFlight. If you’ve piloted an aircraft in the past few years, the odds are high that you’ve used a portable electronic device (PED) for at least part of your pre-flight planning.

While individuals have been quick to adopt mobile technologies, many aircraft operators have been moving into the 21st century at the speed of dial-up — particularly in the helicopter industry, where small fleet sizes can make it difficult to justify the transition to a paperless cockpit. For a private pilot, joining the digital revolution can be as simple as downloading an app, but for a commercial operator, complying with the relevant regulatory guidance is time-consuming and expensive. It’s not surprising that many commercial helicopter operators have delayed the adoption of electronic flight bags (EFBs), figuring that carting some extra paper around is preferable to 12 months of intensive consultation and negotiation with their principal operations inspector.

Those attitudes are changing, however. It’s becoming increasingly difficult for operators to ignore the advantages EFBs can offer, not simply as e-readers for charts and documents, but as essential tools for improving organizational efficiency and safety. When used to their full potential, EFBs can enable operators to streamline and automate any number of cumbersome systems — including billing, record-keeping, and document distribution — in addition to replacing paper and improving situational awareness in the cockpit. Adopting EFBs still isn’t easy, but as a growing number of helicopter operators are finding, these far-reaching benefits can make the process worth it.

By the Book

First of all, what exactly is an EFB? An electronic flight bag has both a hardware component (such as an iPad) and a software component (one or more software applications intended primarily for flight deck or cabin crew). In casual conversation, “EFB” might be used to refer to either or both, which accounts for some of the confusion surrounding the term.

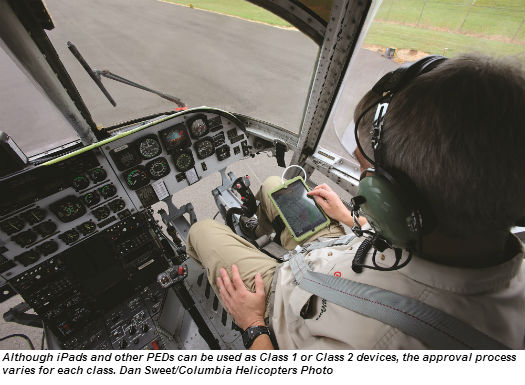

EFBs are defined more precisely in several advisory circulars, including United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) AC 120-76C, which was updated in May of this year, and Transport Canada AC 700-020. Both establish three classes of EFBs. Class 1 and 2 EFBs are portable electronic devices, such as the iPad, that do not have aircraft certification approval for their design or internal components. They differ primarily in how they’re used within the aircraft — while Class 1 EFBs are not mounted in the aircraft, connected to aircraft systems for data, or connected to a dedicated aircraft power supply, Class 2 EFBs may be. Class 3 EFBs, meanwhile, are devices certified in accordance with applicable airworthiness regulations, and thus not part of the commercial off-the-shelf PED revolution.

In addition to defining classes of hardware, the FAA and Transport Canada advisory circulars also set out three types of software applications. Type A software apps are paper replacement applications primarily intended for use during flight planning, on the ground, or during noncritical phases of flight; examples include company manuals and operations specifications, and flight and duty time logs. Type B software apps are paper replacement applications intended for use during all phases of flight; they include apps for calculating performance, and interactive electronic aeronautical charts. Finally, Type C applications are, like Class 3 EFBs, certified in accordance with airworthiness regulations, and include the critical communications and navigation functions found in avionics.

The regulatory approval process for adopting EFBs depends not only on the hardware and software types involved, but also on what type of operations you perform. If you’re a private operator, a public use operator, or your commercial operations are limited, you may not need approval at all. In the U.S., AC 91-78 provides pilots conducting operations under Federal Aviation Regulations (FAR) Part 91 with authorization to use EFBs during all phases of flight operations, provided that the information displayed is the functional equivalent of paper reference material and the information being used for navigation or performance planning is current, up-to-date, and valid. This advisory circular provides pilots with some common-sense guidance on using EFBs — recommending, for example, that a secondary or backup source of aeronautical information be available in the aircraft — but it leaves most of the implementation decisions up to the pilot-in-command.

If you carry passengers for hire, however, don’t expect to get off so easily. AC 120-76C and AC 700- 020 are each more than 30 pages in length, and most of those pages are devoted to describing the EFB approval process for commercial, passenger-carrying operations. You might assume that this process would be simpler for a visual-flight-rules (VFR) helicopter operator than for, say, American Airlines, but you would be wrong. When it comes to EFBs, even small operators must jump through a lot of hoops, satisfying a list of requirements that range from electromagnetic interference (EMI) testing to a carefully documented six-month validation period.

The process that Columbia Helicopters went through to implement iPads — which it uses as Class 1 EFBs for electronic document storage, weight-and balance calculations, and load manifests — is a good example of what’s involved. Based in Aurora, Ore., Columbia operates a fleet of heavy-lift 234 Chinook and 107-II Vertol helicopters on diverse missions around the world, including FAR Part 135 operations for the U.S. government in Afghanistan. Columbia started its EFB program from scratch in early 2011 and obtained regulatory approval in May 2012, using custom software apps tailored to its unique operations. At the time, the company wasn’t aware of any other operators in its market that were using iPads in the cockpit, although it knew that airlines were starting to adopt them.

“The process was lengthy — it took more than a year,” said Columbia Helicopters operations quality manager Christian Boatsman, a pilot and software developer who took the lead on the project. He explained that Columbia worked closely with the FAA throughout the process, and carefully followed the guidance in AC 120-76, actually developing a “compliance matrix” to ensure that the company met all of the advisory circular’s requirements. Along the way, Columbia benefited from its considerable in-house expertise; for example, because Columbia holds the type certificates for the 234 and the 107, its engineers were able to develop their own EMI testing procedures.

According to Boatsman, one of the most involved parts of the process was the six-month validation period, during which time selected flight crews tested EFBs side-by-side with traditional paper reference materials, documenting any issues that arose. And issues did, in fact, arise. Columbia classified errors according to their type (user error, programming error, data discrepancy, version discrepancy) and performed a risk analysis on each problem. Explained Boatsman, “We tried to look at, how can we decrease the chance of that recurring, and also the risk associated with that.” Software applications were tweaked, and databases were corrected. When it came to user errors, Columbia found that most of these were due to inadequate training, so it beefed up its on-site training program and created supplementary training videos. Now, Boatsman said, Columbia’s pilots each undergo around four to six hours of training on EFBs, including scenario-based training sessions in a flight simulator.

Is this process overkill for a VFR helicopter operator? Compared to the ease with which private pilots can start using iPads and other PEDs, it may seem that way. But there’s also an argument to be made for careful, thoughtful integration of EFBs in any company that already relies on well-defined operational procedures, as most commercial helicopter operators do.

“The main part of the approval process under FAA as well as EASA [European Aviation Safety Agency] is adopting appropriate training and operational procedures to safely introduce EFBs into your daily flight operations,” explained Markus Siebert, the Berlin, Germany-based creator of the iPad software application heliEFB. “EFBs are fundamentally changing your flight planning, flight documentation, and record-keeping processes. Those new processes have to be described in appropriate operational procedures in order to receive operational approval for EFBs.”

Thinking Strategically

Given the amount of work involved in obtaining approval for EFBs, it’s not surprising that many of the pioneering users of EFBs in the commercial helicopter industry have been large operators with substantial resources to devote to the task. Among these pioneers have been a number of major offshore oil-and-gas operators, including CHC Helicopter. As previously reported in Vertical (see p.87, Oct-Nov 2011), CHC began developing an EFB system and integrating it into its enterprise resource planning and scheduling systems in early 2011, and is now in the process of deploying iPad-based EFBs on a majority of the 250 helicopters that the company operates in 30 countries around the world. Although CHC was quick to appreciate the iPad’s convenience factor for pilots, its ambitious rollout of EFBs has been driven by a wider vision. For CHC, EFBs are more than just time- and space-savers for the cockpit — they’re tools for standardizing its widely distributed global operations, speeding its billing processes, and enhancing its safety management system.

“[CHC] is a very data-driven organization, in the best sense of the phrase,” remarked Jeff Johnson, VP of business development for Fargo, N.D.-based Appareo Systems, which was hired by CHC to develop a customized flight planning and data distribution application called Mission Manager. According to Johnson, Appareo has designed the app as “very logisticscentric” to assist CHC in flowing information to and from its many far-flung bases. Before and after each mission, data from that flight transfers back to the company in “a very centralized and organized fashion,” where it can tie into maintenance and crew scheduling systems. Johnson noted that the data can also be used to generate quick, accurate customer invoices, which are less likely to be disputed than invoices based on handwritten notes.

PHI, Inc. is another major helicopter operator that has taken an integrated approach to implementing EFBs. PHI began working with the enterprise software company Ramco in 2005 on a custom EFB solution as part of a larger effort to integrate its maintenance, materials, and finance and accounting systems, and extend paperless operations to the cockpit. Refined and updated over the years, this software forms the basis for the off-the-shelf EFB solution that Ramco now offers to other helicopter customers, who are typically also users of its maintenance software. “Maximum benefits come from integrated deployment,” explained Praveen P N, Ramco’s principal consultant for aviation. While large operators like PHI have led the way in this integrated approach, he said, medium-sized operators can also achieve significant efficiencies by fully or partially integrating EFBs with other enterprise systems.

What about smaller operators? That’s where the calculusbecomes more difficult. Large and medium-sized operators often have compelling business cases for adopting EFBs, and can afford to invest in customized software that is tailored to their individual requirements — which are often very different from those of airplane operators for which most aviation apps are designed. “It’s been really, really beneficial to have our own apps,” emphasized Christian Boatsman of Columbia Helicopters, advising other operators who are considering EFBs to “try to find the resources to do it yourself if you can.” Of course, that simply isn’t an option for many on-demand operators with only a handful of helicopters, who may reasonably decide that implementing EFBs isn’t worth the hassle for the sake of a bit of paper-saving.

Their prospects are improving, however, as more software developers are turning their attention to the helicopter industry. Among them is heliEFB’s Markus Siebert, a helicopter pilot himself who has developed his customizable off-the-shelf EFB software specifically for helicopter operators. Created for the iPad, heliEFB offers many of the features found in custom helicopter EFB applications, including flight and fuel planning, weight and balance, load manifest, and flight log functions. The software’s standard application programming interface allows logged data to be transferred to maintenance and flight operations systems, so that helicopter companies of all sizes can achieve the same integration benefits that many large operators have already come to rely on.

According to Siebert, one of heliEFB’s European launch customers has already fielded its first units at five of its 34 air rescue bases, and, at press time, was expecting to receive operational approval under EASA in July. Siebert hopes that deployment in North America will be close behind. “Working closely together with two prospective U.S. launch customers, we will be fielding the first units for FAA operational approval in August,” he told Vertical.

As helicopter-specific EFB software becomes more capable and widely available, it seems inevitable that more helicopter operators will abandon paper for the convenience, efficiency, and potential cost-savings of paper. But even small operators using off-the-shelf apps will get the most out of their EFBs by adopting them as larger operators have — through a careful process driven by well-defined organizational goals.

“You have to be very clear about what you want out of an EFB deployment — are you just reducing paper, or looking for overall efficiency gains?” said Ramco’s Praveen P N, when asked what advice he would give helicopter operators considering an EFB program. “It’s pretty much driven by your vision.”