The helicopter industry in the United States started to takeoff in the 1940s, while the world was still in the throes of war. During this tumultuous time, Igor Sikorsky designed the first practical rotorcraft in the U.S., placing R-4, R-5 and R-6 helicopters into limited production. Not far behind, Arthur M. Young and the Bell Aircraft Corp. were hard at work designing their own helicopter models, and so, too, were likes of

Frank Piasecki, Charles Kaman and a host of others in the northeastern U.S.

Meanwhile, a gifted young teenager out west, in Berkeley, Calif., was poised to enter the helicopter industry and influence future production in a very big way.

Born Nov. 15, 1924, in San Francisco, Calif., Stanley Hiller Jr. — the son of Stanley Hiller Sr., a steamship company owner, distinguished engineer, aviation pioneer, and inventor — learned to fly aircraft literally from his father’s lap. But, the youthful Stan Jr. not only showed an interest in aviation, he demonstrated the skills and mind of an inventor and entrepreneur, as well. As a pre-teen, he salvaged the engine from one of his damaged model airplanes and rebuilt it into a gas-powered model racecar. That invention soon became the Hiller Comet model racecar series — leading to a home-based business that came to gross $100,000 US a year by the time he was 17 — and led to the creation of Hiller Industries.

During this time, he and his father invented a process to increase the strength of the aluminum castings used in the Comets. This in turn led to another new undertaking, making aircraft parts for the military. He also found time to graduate from high school and commence studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

Around this time, he had also begun to take an interest in helicopters, and concluded, after much research, that he could design and build a more efficient rotorcraft than what was available. In 1942, he made the big decision to leave university, with his father’s support, after a disagreement with an instructor over helicopter design.

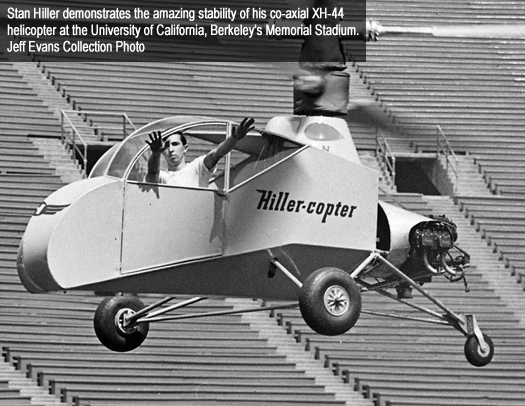

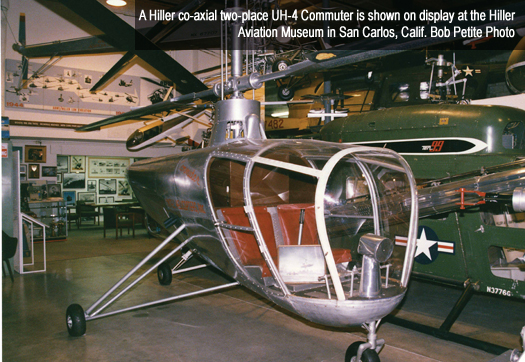

Soon after, the 17-year-old Hiller founded the Hiller Aircraft Co. and brought together a modest team that included a draftsman, a welder and an auto mechanic. They settled into an auto repair shop to build Hiller’s first helicopter — the co-axial, single-place XH-44 Hiller-Copter. However, in addition to having difficulty obtaining parts, the team had trouble acquiring an engine, due to war restrictions. Fortunately, after Hiller made several trips to Washington, D.C., Grover Loening, aeronautical advisor to the U.S. War Production Board, approved the provision of a Franklin 90-horsepower engine for Hiller Aircraft’s test program.

The XH-44, which had metal, co-axial rotor blades and no tail rotor, was ready for ground tests by the fall of 1943. Its first powered run-up was inside the company’s small repair garage and resulted in the glass skylights breaking into pieces due to the airflow from the co-axial rotors. Of course, that was not the program’s only setback: Hiller, who was actually learning how to fly a helicopter during the flight-test process, rolled the XH-44 during an early tethered test. After repairs were completed, he did eventually learn how to control the aircraft. And on July 4, 1944, he successfully flew the XH-44 for the first time; it was the very first co-axial helicopter to fly in the U.S., and the first helicopter to fly in the western U.S.

Henry J. Kaiser, the steel and shipbuilding magnate, was impressed enough with the XH-44 to invest in Stan Jr., and Hiller Aircraft soon became the Hiller-Copter division of Kaiser Cargo. Hiller and his team constructed three two-place, Lycoming-engined, co-axial helicopters, with even stronger metal rotor blades, for the new division. The “marriage,” though, lasted only a year, falling apart when Kaiser refused to increase funding for future production of commercial helicopters (choosing instead to invest his money in automobile production [Kaiser-Frazer and its successors]).

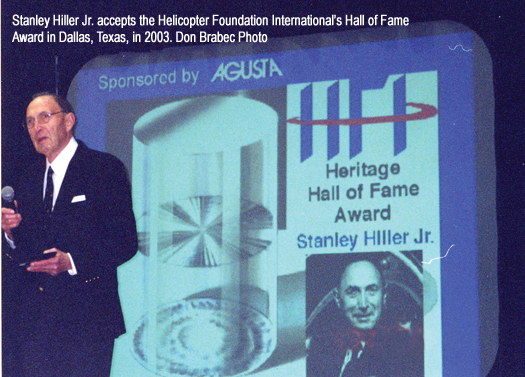

Following the break-up, Hiller founded a new company, United Helicopters, in 1945. There, Hiller created a new, two-place version of his co-axial helicopter design, designating it the UH-4 Commuter. Unfortunately, a near-fatal crash and a lack of the hoped-for civil market interest led to Hiller pursuing other design options. One of those options was the J-5, the first helicopter to use a jet-thrust system to compensate for torque. A later version, the UH-5, featuring a standard tail rotor, was used in 1947 to test Hiller’s “Rotormatic” control system, which featured an overhead control stick connected directly to the control rotors through a simple linkage. This set-up allowed the pilot to control the pitch of the rotor paddles, which then changed the pitch angle of the main rotors, greatly stabilizing the pitch and roll axis, boosting pilot inputs and improving hover control, although it did decrease control response somewhat.

Although they never went into production, those early designs led to the successful Hiller 360/UH-12 series, which was equipped with, among other things, the advanced Rotormatic control system. In its original form, the three-place, all-metal, semi-monocoque 360/UH-12 had a 178-horsepower Franklin engine, a tail rotor and wooden main rotor blades. The Hiller 360X prototype’s cruising speed was advertised as 85 miles an hour, with a range of 212 miles and endurance of 2.2 hours. Gross weight was around 2,200 pounds and useful load was over 700 pounds. U.S. Civil Aeronautics Administration Type Certificate 6-H-1 was received on Oct. 14, 1948, making Hiller Aircraft just the third company in the world (after Bell and Sikorsky — see p.124, Vertical, April-May 2010; and p.108, Vertical, April-May 2012, respectively) to receive approval for manufacturing a commercial helicopter. Not bad for a 23-year-old with no formal education in engineering or aviation!

According to company records, United/Hiller (in the

1940s and 1950s, United successively changed its name to Hiller Helicopters and then to Hiller Aircraft) sold more helicopters commercially during 1948 and 1949 than all other manufacturers combined. About 194 Hiller 360/UH-12As in all were delivered to commercial operators and to the U.S. Army (as the H-23A) and Navy (as the HTE-1) by 1950.

Upgrades and improvements helped the UH-12 continue its commercial success into the 50s and 60s, and the Korean War certainly helped spur greater acceptance and sales of military UH-12 models. In all, by the end of production in 1965, the UH-12 series — including the UH12-B (Army H-23B/Navy HTE-2), UH12-C (Army H-23C), UH-12D (Army H-23D) and UH-12E (the 12E variants became the Army H-23F and H-23G) models — saw over 2,000 units manufactured.

United/Hiller was also a force when it came to research and development; Stanley Hiller was always innovative and forward-thinking. Among the company’s unique aircraft designs were the tip-jet-powered HJ-1 Hornet/YH-32; the ducted-fan 1031 Flying Platform and VZ-1 Pawnee; the ultralight Model 1033/ROE-1 Rotorcycle; and the tiltwing X-18 V/STOL aircraft, which led to the Vought-Hiller-Ryan/Ling-Temco-Vought XC-142.

Although, United/Hiller had seen sales and R&D success, by the 1960s it was in need of a big contract. Hiller himself felt winning the U.S. Army’s light observation helicopter (LOH) competition would be what his company needed to ensure financial stability for many years to come. Unfortunately, after designing and building five prototypes of the Army-designated YOH-5A (Hiller Model 1100), it lost the LOH competition to the Hughes Tool Co.’s aircraft division (later Hughes Helicopters), who had won with a controversial low bid that led to a Hiller protest and the re-opening of bidding a couple of years later (which Bell’s OH-58/JetRanger eventually won).

In May 1964, needing an influx of capital, Stanley Hiller sold his company to Fairchild Aviation of Hagerstown, Md., which renamed its new division Fairchild Hiller. Hiller continued to play a key role there for a few years — and saw to it that the OH-5A would become the commercial FH-1100 (with the first units produced in 1966, and a total of 246 units built by the time production stopped in 1974) — but had already begun being wooed by other interests.

Hiller left Fairchild Hiller in 1968 to start the Hiller Investment Co., a non-hostile, corporate turnaround firm that rescued financially troubled companies. During the next 20-plus years, Hiller turned many companies back to profitability, including G.W. Murphy Industries, which became the Reed Tool Co. and was later acquired by Baker International; Baker International, itself, which later, quite ironically, merged with the Hughes Tool Co. to become the Baker Hughes Corp.; Levolor (now part Newell Rubbermaid Inc.); the Bekins Co.; and York International (now part of Johnson Controls Inc).

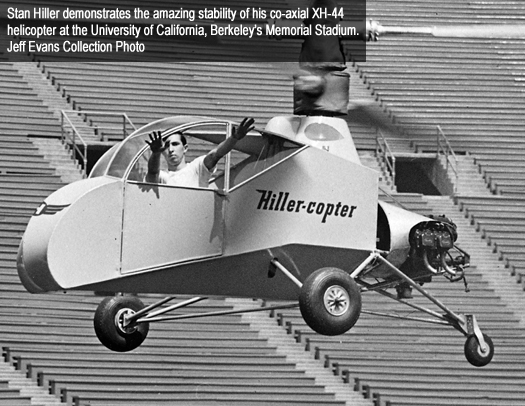

In 1998, after he had retired from his second career, Hiller returned to aviation, founding the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos, Calif., to preserve West Coast aviation history. A few years later, on April 20, 2006, he passed away at his home in Atherton, Calif. — but not before being recognized by several key organizations, including the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, who awarded him its Lifetime Achievement Trophy.

Throughout his career, Hiller Jr. always acknowledged the influence of Stanley Hiller Sr., even once stating, when asked by a reporter how he had achieved so much in his youth, “I was fortunate in my choice of a father.”

Bob Petite is an air attack officer with the Alberta Forest Protection Division. He has over 40 years of experience working on wildfires both on the ground and in the air, utilizing air tankers and helicopters.