For about 70 years, the helicopter has carried cargo and people to where they were required, unhampered by a lack of roads and landing areas, and undeterred by natural or manmade barriers. While most of these loads in the early days were carried internally, some first-generation, North American helicopters did externally sling and carry cargo beneath their fuselages as far back as the late-1940s. And before that, during the Second World War, Germany had used its experimental military Focke-Achgelis Fa 223 Drache (Dragon) transport helicopters, which had twin main rotors on outriggers, to sling cargo net loads and move vehicles and field artillery into formerly inaccessible locations.

Post-war, in North America, Sikorsky was among those companies at the forefront of the move toward creating helicopters with greater lift capability and true transport ability. The first of Sikorsky’s designs to display that capability was the S-55/H-19 utility helicopter, which was introduced in 1950. The S-55 was a leap forward for transport helicopters and achieved a significant amount of success on the military side, as well as a fair degree of success on civil side. But, it wasn’t exactly a heavy-lift helicopter.

The first true ancestor in Sikorsky’s heavy-lift lineage was the piston, twin-engined S-56, which was conceived of in 1950 in response to a United States Navy specification for an assault helicopter. Introduced in 1956, and known as the H-37 in the U.S. Army and the HR2S-1 in the U.S. Navy and Marines, this helicopter was a workhorse that could carry external sling loads of up to 10,000 pounds (4,535 kilograms); hoist up to 2,000 pounds with its internally mounted winch; or carry on board a maximum of 36 troops (26 fully-equipped), three jeeps, light artillery pieces, or 24 stretchers (in an air ambulance role). Unfortunately, while this design did find success in the military, the cost of operating a piston-engined helicopter of this size curtailed interest in it in the commercial market.

A somewhat smaller Sikorsky model that did leave its mark in civil operations and that helped pave the way for heavy-lift commercial helicopters was the S-58/H-34. Introduced in 1954, this new design was smaller and less powerful than the S-56, but larger and more powerful than the S-55 on which it was based. In addition to its incredible success on the military side, it broke new ground on the civil side with its use as both a passenger airliner and in an external cargo-hauling capacity.

An example of the S-58’s great value in civil operations occurred in 1959, in the hands of one of the key operators of the model, Canada’s Okanagan Helicopters (see p.124, Vertical, June-July 2011). Okanagan used its S-58 on a powerline construction job for the Southern California Edison (SCE) Co. in the Soledad Canyon north of Los Angeles (see p.140, Vertical, Feb-Mar 2010). Called “Operation Skyhook,” it marked one of the first major powerline construction projects in North America to utilize a helicopter commercially for medium/heavy-lift work.

Overall, Okanagan’s S-58 was able to save money for SCE and help keep road construction costs to a minimum. The helicopter was able to sling in close to 150 wooden poles with crossarms, dropping them into prepared holes; haul in cement for 15 tower foundations; and transport bundles of steel weighing up to 3,000 pounds.

No Limits

Even with the success of the S-58 in commercial and military lift operations, the model was not a true heavylifter. Plus, Igor Sikorsky realized that regular helicopters, regardless of size and power, were limited in the amount and type of cargo they could carry due to the fact that they had cabins.

As such, as early as 1955, Igor Sikorsky began to talk about the potential of a crane-type helicopter, which didn’t have the limiting factors found in traditional helicopters. “There is no limitation as to the place where the crane helicopter may pick up cargo, or the place where it may lower it,” he remarked. “It has no limit, either, as to the size or bulk of the object to be carried, providing the weight does not exceed the aircraft’s capabilities. Thus, it does not matter what the bulk of the cargo is or how inaccessible the spot of departure or arrival.”

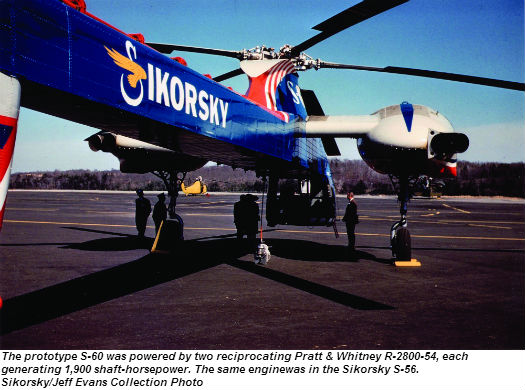

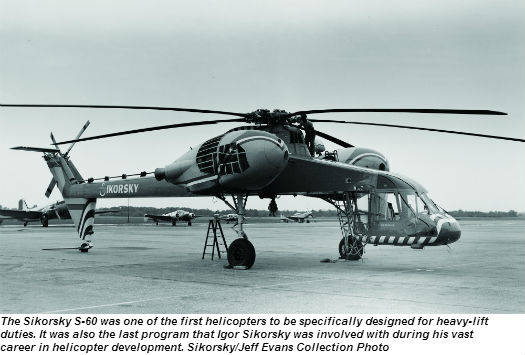

After a full-size mock-up of his crane concept was built in 1956 for evaluation purposes, and later shown to Sikorsky’s parent company, United Aircraft Corp., to obtain project funding, work began on the design of the S-60 research-prototype flying crane (Registration No. N807, Serial No. 60001) in May 1958. Fabrication of the S-60 was completed almost a year later, on March 18, 1959, and its first flight occurred a week later, on March 25.

Built around the proven rotor system, powerplants (two Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp radial engines) and transmissions of the S-56, the S-60 was one of the world’s first helicopters designed specifically for heavy lift — although the even-larger and more powerful Soviet-made Mil Mi-10, based on the huge Mi-6 transport helicopter, followed soon after. (Both, of course, were preceded by the Kellett/Hughes XR/XH-17 “Sky Crane” — see p.124, Vertical, Dec’11-Jan’12 — which first flew in 1952, but never saw production.)

The empty weight of the S-60 was 19,613 pounds. It had a maximum gross weight of 34,500 pounds and a potential payload around 12,000 pounds. The helicopter’s maximum speed was 130 miles per hour (113 knots), and it had a normal cruise speed of 115 m.p.h. Hovering ceiling for the S-60 was 6,800 feet, and its range was 230 nautical miles (265 miles). With no cabin weight, the helicopter not only had additional lifting abilities, but more payload capacity than the similarly sized S-56.

To make best use of that capacity, the S-60 incorporated a cockpit with a unique swivel seat and a second set of controls that enabled the pilot to turn to the rear to supervise, control and observe loading and unloading operations through a spacious, high-visibility windshield. Plus, the S-60 had a multi-purpose, hydraulic-operated, 100-foot cable winch and a free-swiveling cargo hook with a multiple- release mechanism — all of which was designed to simplify cargo handing on the ground and in the air. Finally, the helicopter also incorporated such new innovations as a cable length indicator and built-in scale that specified the weight of each individual load.

As one of the major planned roles for the helicopter would be troop/passenger movement, a platform with troop-type seats was soon constructed and attached to four cables underneath the fuselage. Igor Sikorsky himself — along with three company engineers he had invited to join him — were the first passengers to test out the platform. Surprisingly, that flight was relatively vibration-free and quite stable, even when the S-60 moved into forward flight at 70 knots and climbed to 1,500 feet. In fact, it was stable enough that Igor Sikorsky unbuckled his seatbelt and took an unplanned walk around the small wooden platform — much to the surprise of the pilots! (The next day, a wooden safety railing appeared on the platform.)

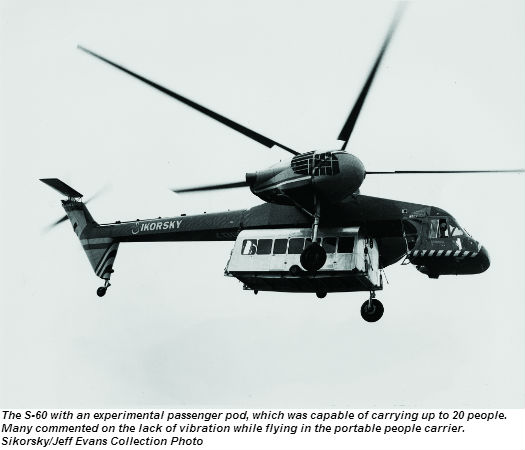

Later, after a 20-passenger pod was tried beneath the fuselage, it was discovered that vibration-free transportation could be achieved with the addition of vertical bungee cords. Subsequent testing determined that a hydraulic attachment system could provide both load pickup and vibration isolation.

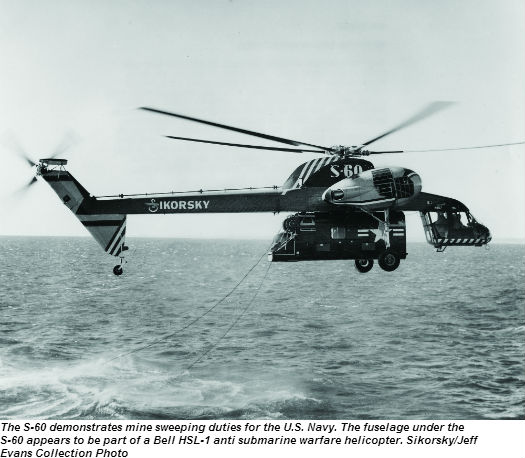

Future uses conceived of for the S-60 included the aforementioned troop movement and insertion with the specially designed pod (which had an eventual planned capacity of up to 40 people); ship-to-shore transport of supplies; minesweeping and towing duties; transporting drill rigs and workers to remote sites; military and civilian construction projects; moving heavy equipment on wildfire operations; hauling timber on logging operations; powerline transmission tower construction; and large-scale search-and-rescue operations.

A New Future

With the success of the initial testing at Sikorsky’s facilities, the U.S. Army then carried out the first military evaluation of the S-60 in August 1959 at Fort Rucker, Ala. Military personnel were impressed with the lack of vibration after flying in the experimental passenger pod, and found that troops and cargo could be loaded and unloaded with ease. The S-60 also demonstrated the slinging of several different vehicles, including trucks and bulldozers; even missiles were carried beneath the flying crane.

With numerous military applications being confirmed or envisioned, including both combat support and transportation of heavy cargo, a tour of Army and Navy bases was conducted over the next few weeks, demonstrating the versatility of the S-60.

The following year brought more demonstrations, along with further development of cargo carrying techniques, minesweeping and towing, and the hoist system. Tests continued into 1961, finally ending on April 3, when the prototype unfortunately crashed during a checkout flight where the control system sensitivity had been set to twice its normal value (to prepare it for further testing and modification by NASA to examine the effect of control sensitivity on precision low-speed maneuvers). The pilots were unhurt, but the helicopter was damaged to the point where it was considered uneconomical to repair.

The wrecked prototype was eventually given to the New England Air Museum in Windsor Locks, Conn. It then quite unfortunately suffered further damage due to a tornado that ripped through the museum, and ended up sitting in pieces for years amongst the trees at the back of the museum. Thankfully, the Connecticut Air & Space Center in Stratford recently undertook the task of restoring it back to display condition. At last report, the cockpit section was expected to be completed later this year, just in time for at least part of this iconic helicopter — the last one Igor Sikorsky is known to have designed and developed — to catch the end of Sikorsky Aircraft’s celebration of 90 incredible years in the U.S.

While the Sikorsky S-60 twin-engine flying crane didn’t end up in production — and wouldn’t have due to the fact that its piston engines were underpowered for its missions — its nearly two years and 335 hours of flighttesting showed that the concept was very viable and could provide the value and versatility Igor Sikorsky envisioned. In fact, by the time of its accident, the company had already begun work on a more-powerful, direct successor to the S-60: the twin-turbine S-64 Skycrane/CH-54 Tarhe, which took its initial flight on May 9, 1962, and went on to become an icon in both civil and military operations.