Dave Repsher’s memory of the accident is spotty.

It was Friday, July 3, 2015, the beginning of a Fourth of July weekend that had brought throngs of visitors to Summit County in the Colorado Rockies. The weather was promising, with a moderate breeze and scattered clouds in a sunny blue sky. For Repsher, a flight nurse with Flight For Life in Frisco, Colorado, it was simply another day at work. Nothing that happened that morning struck him as eventful.

Around 1:30 p.m. local time, Repsher strapped into the left aft seat of the Flight For Life helicopter, an Airbus H125, at the Summit Medical Center Heliport. Seated across from him in the cabin was flight nurse Matt Bowe; at the controls of the aircraft was pilot Pat Mahany. The three of them were headed just a short distance west to Gypsum to make an appearance at a Boy Scout camp. Because it wasn’t a medical mission, “there was no urgency,” Repsher recalled. “The takeoff — the run-up to it — nothing seemed out of the ordinary.”

But at some point during or immediately after takeoff, Repsher realized that something was wrong. Surveillance camera footage of this moment shows the helicopter starting to turn counterclockwise as it lifts from the ground; the rotation continued as it rose higher in the air.

“Matt and I looked at each other, and he got on the intercom and asked Pat if we were OK, and we didn’t hear any answer,” Repsher said. “I was sitting in the left seat and I could see how hard Pat was working, and Matt and I looked back at each other and just cinched down our belts and hung on.”

A witness estimated that the aircraft reached a height of about 100 feet (30 meters) above the ground before it started to descend, still spinning. Thirty-two seconds after takeoff, the aircraft impacted a parking lot and recreational vehicle. Jet fuel spilled from the helicopter’s ruptured fuel tank. In the surveillance video, the first flames of a post-crash fire are visible within seconds.

“I remember an impact,” said Repsher. “I can’t tell you anything about it.” He doesn’t remember being knocked out, but it’s evident from the video that he must have been briefly unconscious. “My first memory was, it was like someone dumped a five-gallon bucket of cold liquid right over my shoulders. Maybe that’s what woke me up, I don’t know, but it felt like this big gush of fluid over me. And then there was fire.”

Repsher didn’t understand where he was, or what was happening to him. A door from the helicopter was lying on him; he pushed it off and began running, his flight suit drenched in fuel and on fire. “I didn’t know where I was running to, I didn’t know where anything was, I was just gone,” he recalled. “I took in a couple big breaths of smoke and flame. I remember a guy yelling at me to get down on the ground and roll. And I guess I rolled down a hill, and here’s this poor guy, throwing dirt on me, trying to get the fire out.”

Summit Medical Center personnel arrived and put Repsher on a scoop stretcher, then began running with him toward the emergency room (ER). He was still disoriented, but sufficiently aware by that point to know he was in bad shape.

“As they were taking me in, I told them they were going to have to intubate me, because I knew I took in that much smoke. I was starting to feel things at that point. I had my hands up in front of me as I was on the backboard and I could just see the skin sloughing off my hands.”

Repsher was so badly burned that ER personnel struggled to find a place to insert an IV. “They eventually got the IV,” he said. “I asked them to give me as much ketamine as they had. Before they did, I looked up at one of the nurses and said, ‘Tell Amanda I love her.’ I knew what was going to happen; I knew I was in trouble. Then it was black for five-and-a-half months.”

A defining moment

That summer day was a turning point not only for Repsher, but for the entire helicopter industry. Horrific images of the accident and post-crash fire galvanized action around crash-resistant fuel systems (CRFS) in a way that decades of dry accident investigation reports had failed to do.

A few months after the crash, the Federal Aviation Administration convened a Rotorcraft Occupant Protection Working Group to study the regulatory loopholes that had allowed the Flight For Life H125 to be built without crash safety protections that had been mandated in 1989 and 1994. Meanwhile, Airbus Helicopters and Vector Aerospace (now StandardAero) began working on CRFS retrofit solutions for H125 and legacy AS350 series aircraft, and Airbus is now in the process of incorporating CRFS as standard equipment on all new H125s in the global fleet.

Bowe survived the accident with serious injuries. Mahany died of blunt force trauma and thermal injuries a short time after the crash, and in the years since his widow, Karen, has become an outspoken advocate for crash safety. Only recently, however, has Repsher been in a position to champion her efforts. His recovery from the accident, aided by his wife Amanda, has been a harrowing mental and physical journey; a medical saga that continues today, and will for the rest of his life.

It’s not something that Repsher ever expected. A Summit County native, Repsher grew up with a passion for the outdoors that he supported through a career in emergency medical services (EMS). His first exposure to helicopters as a possible avenue for that career came when he was working ski patrol. He recalled being on the side of a mountain, “up to his neck” treating a patient, when an air ambulance arrived.

“Here come these people out of the helicopter, James Bond-esque, just cool, calm, collected, and they come grab your patient and fly away. It’s just something that really impressed me, and something that I wanted to aspire to do possibly, someday.”

The further Repsher progressed in his EMS career, the greater the draw became. He completed nursing school, which positioned him to join the Flight For Life team when an opening became available in 2012. Once he started, the job was everything he expected it to be. “It was the best job I ever had; I miss it today,” he said. “Not to be arrogant, but I was very proud of what I was doing. To be able to serve the region is a great honor.”

Although Repsher was aware of the inherent risks involved in flying, he said he never perceived himself to be in danger.

“Right from day one, I felt there was an incredible culture of safety at Flight For Life,” he recalled. “No corners were cut, when something was due it was done, when something didn’t add up it was taken out of service, and choosing missions was the same way. If there was anything questionable, or if weather might be moving in, or if we might be able to make it one way and maybe not back, we didn’t go. And I had absolute, 100 percent, total faith in all our pilots to make the right choices, like they always did.”

Amanda — who is also a nurse and paramedic, although not a flight nurse — was a little more acutely aware of the risks, because one of her paramedic trainers had been killed in an air medical helicopter crash. But she and Dave took it for granted that he was safer in the air than on a ground ambulance. Amanda’s work involved extensive road travel, and “I told myself that statistically, like Dave said, I was more at risk driving around the state for my job than he was in a helicopter. But I guess maybe not.”

‘I knew’

Amanda and Dave have been together since 1999; like him, she is passionate about the outdoors, particularly river rafting. A few days before the accident, the Repshers had been on a rafting trip on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho. “I remember thinking on the trip, ‘Wow, this is one of my favorite river trips ever,'” she said. “We were just so lucky to have an amazing time.”

On July 3, 2015, Amanda was still on her days off from work. She had gone to the gym and the grocery store and was sitting down to eat a sandwich when her phone rang. It was their friend George. “He said, ‘Amanda, I heard that there was a helicopter that crashed in Frisco but that everybody walked away.'” He didn’t tell her that it was the Flight For Life helicopter.

Amanda called Dave’s cell phone. He didn’t answer, but that wasn’t unusual, since he often left his phone in his bag while at work. She called the nurses’ office line at Flight For Life; there was no answer there, either. She was looking up the number for Flight For Life dispatch when her phone rang again — this time it was their friend T.R., who worked at Summit Medical Center.

“As soon as I saw his caller ID, I knew,” Amanda said. “I picked up the phone and I said, ‘You tell me now, what.’ And he said, ‘He’s alive, we’re intubating him now.’ I just completely fell apart, I felt like I couldn’t breathe, and I just said, ‘You’ve got to get me to the hospital, now.'”

While the ambulance supervisor headed to the Repshers’ house, Amanda called Dave’s mother, Marilyn, and stepfather, Dave Raymond, who lived just a couple of miles away. They met her at her home and jumped in with the ambulance supervisor for the ride to the hospital. Summit County was bursting at the seams with people for the holiday weekend; traffic was excruciatingly slow. Finally, they arrived at the hospital, and Amanda ran into the ER.

“I got to Dave’s room, and I took one look at him,” she said, and paused. “I used to work at the burn center in the ER and I know what a 90 percent burn looks like when they first come in. And I took one look at him, and I knew. I looked at his hands and they were just so bad.”

Another helicopter was already on its way to transport Dave to the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora, just east of Denver. Amanda knew that she wouldn’t be allowed to fly with him, but she had to ask anyway, because she feared he wouldn’t survive much longer.

“They got him all packaged up and we went to the helipad and loaded him in and it was starting to rain, and the winds were blowing,” she recollected. “Peter the chief flight nurse was there holding onto me and I’m like, ‘Peter, are we really putting him back in a helicopter right now?’ But the whole time in my brain I knew that that was his only chance of survival, because he had to get to the burn center.”

By the time Amanda arrived in Aurora a few hours later, Dave had been transferred to the burn center’s “tub room,” where the most severe burn victims have their wounds cleaned and treated. It can be a traumatic sight for loved ones to witness, which is why the tub room is generally off limits to them. But because of Amanda’s background in critical care nursing, she was allowed in.

“Dave was back there for about four hours, and that’s when they came up with the determination that he was 90 percent burned,” she said. “When they first told us, I came out, I was outside with Marilyn when they first started estimating and we just grabbed each other and started crying. I just knew it was going to be against all odds for him to even make it through the night. But he did. And he’s here.”

Day by day

Amanda had no way of knowing it at the time, but Dave would be in the University Hospital for the next 397 days. She would be by his side every one of those days, not leaving even for her father’s funeral.

Dave began talking on day 42 of his hospital stay, but not with conscious awareness. Amanda didn’t know if he would ever truly “wake up,” but she knew that she wanted to be there if he did.

“One of my biggest fears before him waking up [was] what he was going to feel like and what his perception would be,” she said. “I talked to some other burn survivors. One had told me that his first recollection of the hospital was seeing someone cleaning his room, and I was like, ‘That’s not going to be Dave. When he wakes up, he’s going to know that we’re here, and we love him.'”

That moment finally happened on Dec. 14, 2015. “It was a bizarre thing,” Dave recalled. “I describe it as like a camera shutter opening. For me it was just from black to light across the eyes, and I was awake.”

“It was crazy,” Amanda said. “I knew the second he woke up, because he looked me straight in the eye, and for five-and-a-half months he had not done that.”

Even with Amanda at his side, the experience of waking up was terrifying for Dave. He had the perception that he couldn’t move. He couldn’t talk, because he had a tracheostomy, and the speaking valve was not on. “I was scared,” he said. “I didn’t know what to do. I knew I didn’t want to be bedridden and unable to communicate. I wasn’t sure I wanted to keep going on.”

Eventually his speaking valve was attached, and he was able to voice a few words. Within a few days, he was able to spend hours conversing with Amanda (as she put it, “We had a lot of catching up to do!”). But his progress from there was unsteady. He would battle septic shock for another four months, alternating between periods of clarity and disturbing hallucinations. During those times when he was conscious, he was often in excruciating pain.

“It came time to try to get up out of bed and move, and I can’t begin to describe the amount of pain,” he said. “The pain was so bad that you couldn’t give medication for it, it wouldn’t take the pain away, unless I was completely unconscious. [So] I’d do as much as I could until I literally couldn’t stand any more, and I’d slump back in bed and sleep for a couple of hours.”

Before the accident, Dave had been 180 pounds (82 kilograms) of muscle. In the burn unit, he wasted away to just 89 pounds (40 kilograms). His muscles had atrophied to the point that he had to re-learn the most basic physical tasks from the beginning, even swallowing. From the time of his first swallow evaluation, it was six months of daily swallowing exercises before he was allowed to eat.

“It was things like that in every dimension,” Dave said, “every body system starting over to try to learn how to function again, and making a decision at that time, ‘Can I go through life, do I want to go through life, knowing that I can never eat again? Can I go through life knowing that I may not be able to get out of bed, and I’m going to be 100 percent dependent for everything? Can I go through life in pain? Can I go through life not being able to get outside and do anything that I like to do?'”

Those are the decisions that faced him every day that he wasn’t hallucinating. Somehow, he made the decision each day to keep going on.

“I don’t recall it ever being a conscious decision, it was just something that I did,” he said. “And honestly it had everything to do with Amanda. I wouldn’t be here without her. . . . She brought me through.”

Focused on the future

Thirteen months after he was admitted to University Hospital, Repsher was discharged. But his medical ordeal was far from over. His health remained precarious, particularly because his intense antibiotics regimen had destroyed his kidneys. Five nights a week, Amanda, who had become his primary caregiver, administered dialysis at the small apartment she had rented for them close to the hospital in Aurora.

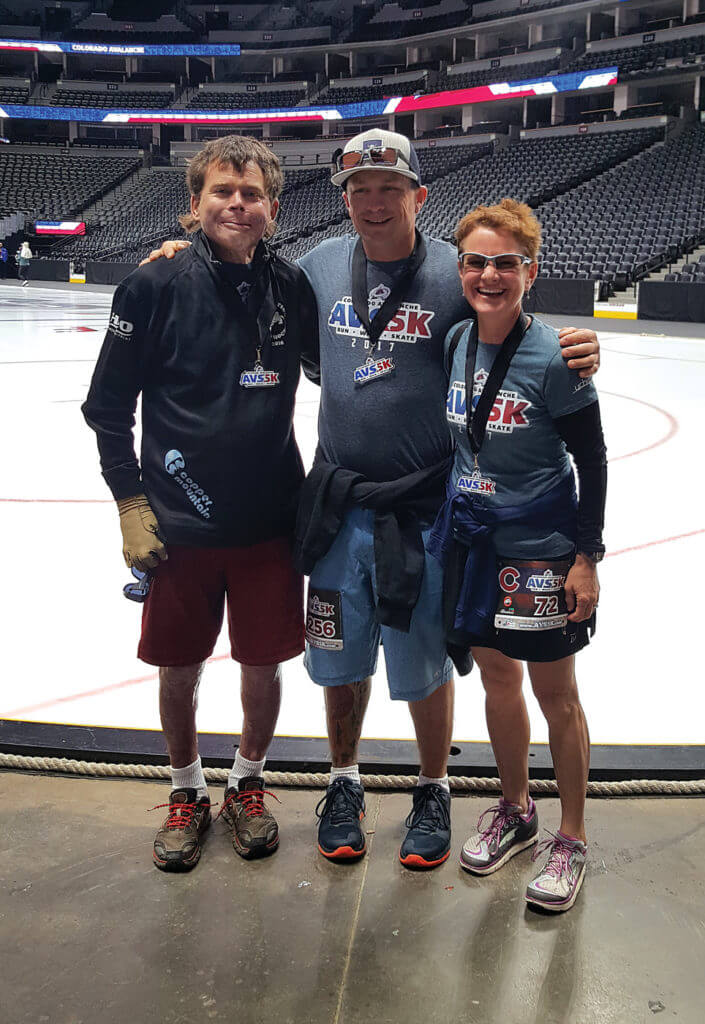

An acquaintance of Dave’s mother named Matt Martinez had heard about Dave’s ordeal and decided he wanted to help. He volunteered as a kidney donor; incredibly, he and Dave were a near-perfect match. In August 2017, Dave received the kidney transplant that gave him a new lease on life. These days, he is still in and out of the hospital with various complications and surgeries, but he is more active, and looking forward to the prospect of finally moving home to Summit County. He is humbled by Martinez’s selfless act.

“The silver lining, or the outcome or the benefit of all this, is seeing the good side of humanity,” Dave said. “Unfortunately it usually takes something tragic to get people together, but it’s been a really neat experience, a beautiful experience from our perspective, to just see what people can do for each other, and the impact that it makes.”

The National Transportation Safety Board investigation into the Flight For Life accident highlighted issues with the design of the H125’s dual hydraulic system, as well as the lack of a CRFS and crashworthy crew seats in the accident aircraft. Earlier this year, the Repshers received a $100 million settlement from Airbus Helicopters and Air Methods, the operator of the helicopter.

According to Amanda, that staggering sum was largely determined by the severity of Dave’s injuries, which have already resulted in $20 million in medical bills, and may cost another $40 million over his lifetime. But it has also given the Repshers the ability to establish a foundation that, in the future, will help them contribute to charitable causes including helicopter safety, organ donation, and supporting burn survivors.

“Dave can help, just be an inspiration to so many people,” Amanda said. “When he was in the ICU, [a burn survivor] who was 87 percent burned would come in, and just seeing her was so amazing for me. I was like, ‘It’s possible.'”

Dave hopes that his story will help drive change in the helicopter industry, so that no one else will similarly suffer in a preventable post-crash fire. But he’s trying not to dwell on the fact that his injuries were avoidable.

“I don’t want to become angry, I don’t want to be that person — it just doesn’t serve anyone well, especially myself,” he said. “I’d rather focus my energy on trying to improve things for the next person. If all of this just boils down to helping one other person walk away from something, then it’s all worth it.”

Interview with helicopter post-crash fire survivor from MHM Media on Vimeo.

Inspired by Dave’s approach, Amanda is taking a similarly forward-looking attitude.

“When you’re blessed enough in this life to find someone that you want to share your life with, and have that true love and that partnership, and then to be given the gift to have it still after what we’ve gone through — you know it makes you just want to live life. And that’s what it’s about, to experience love and share love,” she said.

An incredible story about an amazing man…and his wife.

Meant to say, “and his strong, caring wife.”

You are such and strong and brave man, I admire your courage

Thank you for sharing this Story

Dave and Amanda have incredible courage and a story that defies all odds. I was in a hard landing/crash on my hospital’s property in 2002, and we all walked away thanks to the incredible skill of the PIC (pilot in charge), Chris Basset, in landing looking at an awning, several trees and light poles!. I thanked him then for saving my life, as we all walked away. My door was the only one that would not open, so I had to crawl over a specially built toddler stretcher that gave me about a 2 feet of room from the helo ceiling (not easy in a flight suit with a helmet on). But praise God, no one was seriously injured. Someone asked why I kept doing the job of a flight nurse, and my answer was, “because when I do transports of critical babies and children, I feel God’s pleasure”- taken from the movie “Chariots of Fire”, who when asked by his sister if he had forgotten God’s call to be a missionary, he said, No, but God also made me fast and when I run I feel God’s pleasure. (He was training for the 1936 Olympics)

I live in Frisco and remember this day like it just happened. My family was visiting from Longmont. There’re no words to describe these moment. Glad you pulles through with your wife by your side. God is good. Keep up the good work.

The AStars, AS350/H125, regardless of who owns/flys it, they all need to undergo mandatory retrofit of the fuel tank and crash worthy seats, the AStar I flew on had antiquated seats and seat restraints and the company, wouldn’t retrofit the fuel system because FAA granted them an extension for years, because it would cost too much. So here they are paying out millions now instead of doing what makes common sense and do regard for the crew.