Pioneering helicopter pilot Phillip Hugh Fillingham was born in the small country village of Cobham in Surrey England, some 20 miles southwest of London, in May 1918. As a young lad, Fillingham became interested in aviation, awed by the huge dirigibles and growing number of fixed-wing aircraft that flew so low and slow that pilots and passengers sometimes even waved to kids on the ground. Like many youngsters, he began building and flying model airplanes, and he maintained this interest all through his teenage years. Unfortunately, his dream of becoming a pilot would have to wait, as he could not afford the cost of lessons.

Fillingham in fact ended up as far away from being a pilot in England as one could imagine: when the Second World War broke out in 1939, he was a bank clerk in Rio Gallegos, Argentina, on the far southern tip of South America.

After following the coverage of the Battle of Britain in 1940, however, Fillingham decided he wanted to become a Spitfire pilot and volunteered for the Royal Air Force (RAF). However, due to various restrictions, he was unable to return to England until 1943. On arrival, he was told that the RAF only wanted aircrew and had little need for pilots. Undaunted, he crossed the street and walked into the Royal Navy’s recruiting office. There, Fillingham found he was in luck: the Navy’s Fleet Air Arm was still accepting applications for both pilots and observers. “I quickly put my name down and that is how I became a pilot,” recalled Fillingham in a phone interview.

Fillingham received his boot camp training at Royal Naval Air Station (RNAS) Portsmouth, England, on HMS St. Vincent in September 1944. He was then sent to Canada in December for initial flying instruction at the Number 13 Elementary Flying Training School in St-Eugène, Ont., (some 65 miles east of Ottawa) and soloed on a Royal Canadian Air Force Fairchild PT-19 Cornell on Jan. 5, 1945, after only a little over nine hours of dual training. Several more months of additional flight training, on the North American AT-6 Harvard, followed, with Fillingham receiving his “wings” on June 11, along with the Admiralty Award as the best all-around trainee on the No. 129 Pilots Course in Kingston, Ont. He even found time to get married to a Canadian girl, prior to returning to England for more advanced training at RAF Station Ternhill. But, soon after his return, the war came to an end and a different path for his piloting career would emerge.

In March 1946, Fillingham was posted to the No.1 Operational Flying School RNAS Rattray in Scotland for flight training on the Fairey Firefly Mk1. He then gained deck landing experience and soon graduated to landing on Royal Navy carriers. This led to his posting in 1947 with 816 Squadron aboard HMS Ocean out of Malta in the Mediterranean Sea, where he would carry out 162 deck landings… and encounter a new kind of aircraft that would change his life.

The aircraft was a United States Navy HO3S-1 (Sikorsky S-51), stationed on the visiting carrier USS Philippine Sea, and it was the first time Fillingham had seen a helicopter. With the subsequent disbanding of 816 Squadron in 1948, he decided to see if he could obtain instruction on rotary-wing aircraft. “I made the request and soon found out that I was approved for conversion to helicopters,” said Fillingham. “Nov. 2, 1948, I joined 705 Squadron, HMS Siskin at RNAS Gosport in England for my initial helicopter training.”

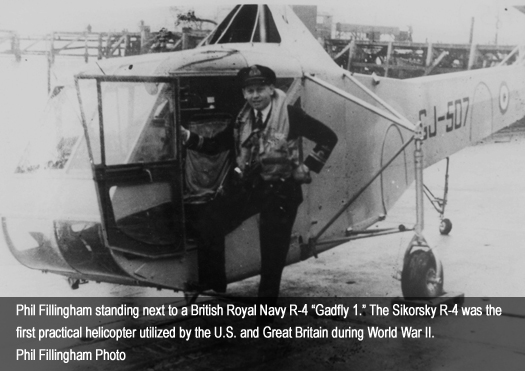

Then, as Fillingham recalled: “After four hours 30 minutes of dual instruction on the Sikorsky R-4, I made my first helicopter solo on KL 111 on Nov. 17, 1948. My main helicopter instructor was Lieut. Ken Reed. [On Feb. 1, 1947, Reed made the first official helicopter deck landing on a Royal Navy ship, landing an R-4B on the HMS Vanguard off the Isle of Portland, England.] The solo checkout consisted [of] my instructor getting on and off the helicopter while I held it stable in a hover. . . . Six weeks later, I was assigned to the Royal Navy Portland Dockyard – Detached Flight as officer in charge of the helicopter unit.

Over the next eight months, Fillingham received additional experience on the R-4, carrying out local flying, torpedo trials, radar calibration, air and radio tests, personnel transportation, photography requests, search and rescue duties, demonstrations, autorotation practice, and dual helicopter flights. In August 1949, he was posted to RAF Station Beaulieu AFEE (Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment) in Hampshire, England, attached to the Ministry of Supply as a helicopter test pilot.

At Beaulieu, under the guidance of RAF Squadron Leader John Cable, Fillingham carried out additional flight testing on Sikorsky R-4, R-6 and S-51, plus the new British Bristol 171 Sycamore helicopter. (Cable was an early autogiro and Sikorsky R-4 pilot; he later lost his life in the crash of the Cierva Air Horse helicopter during June 1950.) One major task for Fillingham involved the testing of autorotation performance in both the R-4 and R-6. He even test flew an instrumented R-4 under the hood and commenced dual R-6 flight instruction with several new Navy students.

By early 1950, Fillingham had accumulated just over 300 hours on helicopters, and in May, with his “short service commission” coming to an end, Fillingham made the decision to immigrate to Canada.

As luck would have it, Spartan Air Services out of Ottawa, Ont., were looking for a pilot. Fillingham was hired in July 1950 and received dual instruction on Spartan’s Bell 47D, CF-FHM, from Bill Johnson. In August, Fillingham was sent to Bell Aircraft in Niagara Falls, N.Y., for further instruction on the Bell 47. “One of my instructors was Floyd Carlson,” said Fillingham. “I received just over nine hours on the Bell 47 between Aug. 18 and Aug. 24. . . . By the end of the month, I was a bush pilot at work in Knob Lake [in] Labrador, flying the Bell 47D, CF-FHM. Spartan was carrying out topographical mapping surveys for the Canadian government. We lived in tents, washed in and drew our drinking water from the lake.”

Next, Fillingham flew a Bell 47D-1, CF-GVV, during February and March 1951, under contract to Hollinger Ungava in Quebec during the early construction of the new rail line from Sept-Îles north to Labrador. “Winter operations were new to me,” said Fillingham. “We covered the helicopter each night, put on blade covers, and in the morning it took about 30 minutes from the portable heater to thaw out the helicopter before it would start. Our floats used to freeze to the ground overnight, so we learned to land on wooden planks instead.”

In addition to the cold, there was the Bell 47’s fan belt problems: “Sometimes the fan belts would fail in as little of three hours operations.” Fillingham in fact had to make his first forced landing in a helicopter due to a fan belt failure while over a forested area. Fortunately, the cold kept the cylinder head temperature down long enough that he was able to get to an open spot on a nearby frozen river.

In June 1951, Fillingham was working in Newfoundland, carrying out barometer traverse surveys, when he had to carry out another forced landing, this one due to a fuel line break. Although his autorotation into trees wrecked the helicopter, both he and his passenger walked away unhurt.

In late 1952, Fillingham left Spartan Air Services for a new venture: flying helicopters in the jungles of Venezuela and Columbia on geodetic surveys. Here, he was introduced to mountain flying with the Bell 47D-1, and made his own first foray into public relations: “The villagers had never before seen a helicopter. I was forced to carry a stick to ward off the local children from climbing over the tail boom while the rotor still turned! Taking off in 106 F [41 C] heat with a 400-pound load from a tiny landing area taxed our flying techniques to the max.” Add in jungle canopies, seemingly unobtainable mountain-top landing spots and ever-present spark-plug fouling on the No.5 cylinder, and Fillingham was experiencing advanced flight training the hard way.

In September 1953, Fillingham joined Petroleum-Bell Helicopters (later Petroleum Helicopters Inc., now PHI) in Lafayette, La., beginning an 11-year relationship with the oil exploration services company. He flew helicopters on seismic and gravity-meter exploration, supported offshore exploration and production, went back to Colombia on seismic operations (always wondering if he’d be attacked by ever-present local bandits), and did mountain operations in California and Alaska — sometimes landing at seemingly impossible altitudes with techniques that were essentially semi-controlled crashes. During this time, he flew an array of helicopters, including various Bell 47 models, Sikorsky S-55s and S-62s, the Sud Aviation Allouete ll, and the Hiller 12E, learning to overcome the limitations of each, and the challenges created by the unsuitable settings they were placed in.

In 1964, he moved on to flying Bell 47J-2As with the Tenneco Gas Transmission Co. in Houma, La., patrolling pipelines and doing in- and offshore personnel transport. By 1967, he was flying the new turbine Bell 206 JetRanger that replaced the Bell 47s (and the Cessna 185 Amphibian he also flew on duty relief). In 1973 he converted to the newly purchased twin-engine MBB Bo.105s and became Houma base chief pilot. By 1978, having reached his 60th birthday, Fillingham had to retire from Tenneco, but this did not keep him from his love of helicopter flying.

Fillingham soon found other new flying horizons, including being a personal pilot for a millionaire coal miner. After a disagreement about safety (the millionaire thought his JetRanger could fly in any weather, day or night), Fillingham started flying for several small companies on various government contracts, including a few where his daughter drove the refuelling truck and was his crew chief.

By 1981, Fillingham had decided to retire from flying for good. Appropriately, his last mission was one to remember, and came while flying a JetRanger for the U.S. Forest Service in Jackson Hole, Wyo., a contract that also included working for the U.S. National Park Service: “The most challenging job was working for the Park Service every weekend, when it was not unusual for amateur climbers to get lost or to fall in the Grand Teton Mountains,” he said. “I capped my 33 years of helicopter flying by rescuing a climber who had fallen and was trapped on a shelf at 10,800 feet. There was no place to land, so we slung a stretcher on a long line into reach of his rescuers and flew him to the hospital in that precarious manner. For this, I was given a framed Certificate of Commendation by the Park Service and the Forest Service.”

By the time he hung up his headset, Fillingham had logged 13,674 hours of hard-flown helicopter flight time (and 581 hours of fixed-wing time). After retiring, and until recent medical concerns curtailed his activities, he continued to contribute to the industry through his volunteer work at the Helicopter Association International’s Heli-Expo conventions and annual Twirly Birds meetings. In fact, he was awarded the Twirly Birds’ Les Morris Award on March 15, 2004, for his dedicated service to the helicopter industry.

Said Fillingham, “I was not a ‘big wheel’ in the helicopter industry . . . only a ‘foot soldier’ that went out on a job, did good work, [and gained] knowledge and experience to do a better one the next time out.” While he may not want to take credit for his efforts, the rest of us in the industry can at least point out that it was early rotary-wing pilots like Phil Fillingham that helped carry this industry forward from its first uncertain steps in the late 1940s. This true helicopter pioneer, now 94 years of age, reminds us of just how far the industry has come and how much pilots of his generation had to overcome just to do their jobs.

Bob Petite is an air attack officer with the Alberta Forest Protection Division. He has over 40 years of experience working on wildfires both on the ground and in the air, utilizing air tankers and helicopters.