Today, when an accident or injury occurs on an offshore oil platform or service vessel in the Gulf of Mexico, off Newfoundland’s coast or in the Arctic regions, it’s increasingly likely that the first helicopter on the scene will be civilian-crewed.

The use of rescue helicopters got a lift some 67 years ago, on Nov. 29, 1945, when a Sikorsky R-5 piloted by Dimitry (Jimmy) Viner — Igor Sikorsky’s nephew — performed the first helicopter hoist rescue in aviation history. Viner and co-pilot Capt. Jack Beighle of the United States Army Air Forces pulled two men from a grounded oil barge in Long Island Sound off Fairfield, Connecticut.

Since then, U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) helicopters have responded to tens of thousands of maritime emergencies.

But the rapid expansion of deepwater, ultra-deep and frontier oil-and-gas exploration activity since the mid-1990s has, as a by-product, created a need for first-response capabilities beyond those for which the RCAF and USCG were originally designed or equipped. As noted by the National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling: “Modern oil-and-gas drilling rigs and producing platforms . . . for all their productivity . . . expose their crews to the risks of injury or death if not properly operated and maintained — risks compounded for operations conducted in progressively deeper waters, ever farther from shore.”

Dedicated 24-hour commercially operated SAR helicopter can now be found around the world, and has in fact been in operation around the UK for over 40 years. But it’s only relatively recently — beginning in 1996 in Canada, and 2005 in the U.S. — that the North American offshore oil industry joined the wider international community in deploying a range of assets, including dedicated, long-range, search-and-rescue (SAR) helicopters (provided either under existing contracts, or via specialized, regionally-based SAR operators) and boats (for mass evacuation) to better suit their evolving first-response requirements.

These deployments have become even more critical as, when oil prices climbed from 2003 to 2008 (peaking at over $147 US a barrel), so did the industry’s interest in exploring frontier areas off the north coast of Alaska and the Northwest Territories, and the west coast of Greenland.

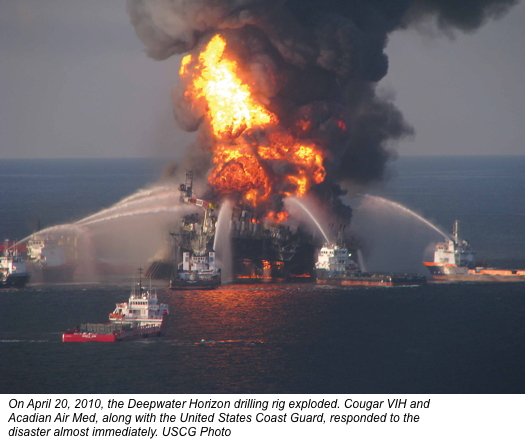

And, following the crash of Cougar Flight 491 off Newfoundland in March 2009, and the Deepwater Horizon incident in April 2010, new offshore safety regulations and risk management policies increased the requirement for first-response helicopters to meet “worst case analysis” contingency response plans.

This past summer, three North American helicopter operators — Cougar Helicopters, Era Helicopters and VIH Cougar Helicopters — had four AgustaWestland AW139s and three Sikorsky S-92s on first-response contracts serving offshore rigs and vessels working in the North Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Arctic Ocean. Although these helicopters represent only about 1.4 percent of the approximately 500 helicopters flying offshore in Canada and the U.S., their civilian pilots, hoist operators, paramedics and rescue swimmers are a most welcome sight (especially when an emergency arises).

Atlantic Canada

Helicopter-supported offshore oil-and-gas exploration began off Nova Scotia in 1969 and off Newfoundland and Labrador in 1971.

The royal commission into the capsizing of the semi-submersible Ocean Ranger drilling rig that killed all 84 crewmembers in February 1982 set the ground rules for future offshore development in Canada. It also highlighted shortcomings such as the lack of a SAR helicopter at the nearest airport (in this case St. John’s, Nfld.).

By June 1997, when Cougar Helicopters had begun flying Eurocopter AS332L Super Pumas from St. John’s to the new Exxon Mobil Hibernia production platform some 200 miles (320 kilometers) offshore, things had changed.

“A civilian, first-response SAR capability was part of our original Hibernia offshore contract,” recalled Cougar general manager Hank Williams. “The Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board [C-NLOPB] required that our crew-change helicopters be available for first-response missions, because the nearest military SAR unit was [another] hour away in Gander.

“We didn’t have a dedicated aircraft when we started, but had to reconfigure a passenger-carrying aircraft. The pilots who flew passenger flights were cross-trained to fly SAR missions, but we had dedicated rescue specialists in the back of the helicopter from the beginning.”

The Super Pumas had to be wheels-up in 60 minutes. This time was needed to remove the passenger seats and install the first-response equipment, including a hoist, a rescue door, Stokes litter, rescue basket and medical supplies. (Interestingly, Cougar provided Canada’s first civilian SAR service, using a Sikorsky S-76A, on fisheries patrols off Nova Scotia from 1991 to 1994.)

Soon after, in 1998 and 2002, respectively, Cougar won contracts to support Petro-Canada’s (later Suncor Energy’s) Terra Nova oilfield and Husky Energy’s White Rose field. Then, in 2005, a year after the VIH bought Cougar, it introduced the Sikorsky S-92, to better support the Terra Nova, Hibernia and White Rose contracts and the growing offshore exploration demand.

As the new production programs and exploration rigs steadily increased off the east coast of Newfoundland, Cougar became a critical transportation lifeline for the 700 to 1,000 people that were working offshore at any one time, and provided first-response helicopter capability for all the offshore oil companies.

“In about 2008, we began talking with our oil industry customers about providing an enhanced first-response capability,” said Williams. “This is when we started discussing a dedicated aircraft to shorten response times and provide an aircraft for expanded crew training.”

At the time, Cougar had three or four S-92s based in St. John’s to support production and exploration activity, with SAR-configured S-61Ns stationed in St. John’s between seasonal exploration support contracts in other regions.

With the C-NLOPB’s Offshore Helicopter Safety Inquiry recommending the introduction of a 24-hour first-response helicopter in St. John’s, Cougar launched its service in March 2010 to support three Grand Banks offshore oil projects and all of their associated vessels and exploration rigs.

In late 2011, the Canadian certification of the SAR automatic flight control system for the S-92 allowed Cougar crews to conduct night winching operations. A purpose-built SAR facility, complete with crew accommodation, then opened in spring 2012, reducing Cougar’s response times to 20 minutes.

As for the aircraft itself, Cougar’s SAR S-92 is equipped with such rescue equipment as a Goodrich dual rescue hoist, forward-looking infrared (FLIR) imaging system with dedicated FLIR workstation, 30-million candle power NightSun searchlight, Stokes litter, triple-level stacker stretcher system, marine salvage pumps, air droppable survival kits (known in the industry as SKADs), auxiliary fuel tank and advanced life support equipment (night vision goggles will be added later this year).

The S-92 crew includes two pilots, a hoist operator and two rescue specialists. In all, Cougar has 13 full-time pilots and 16 rescue specialists that work 12-hour shifts on the same three weeks on/three weeks off schedule as oil workers, with the S-92 flying 60 to 80 training hours a month. Overall, said Williams, “The first-response role is comprised of both SAR and medevac missions.”

Cougar’s new mandate — following the Bristow Group’s recent purchase of a minority stake in the company — is to pursue new SAR business in Canada, Greenland and the Arctic. In particular, said Williams, “One of the opportunities we see is providing civilian SAR on contract to the government . . . for example, [if] there was an effort to expand SAR capabilities off Newfoundland and Labrador.”

Gulf of Mexico

Deepwater and ultra-deep oil production in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM) surpassed shallow-water production around 1998, with 17 deepwater production facilities installed between 1979 and 1999, and another 30 between 2000 and 2010. By late January 2013, a record 51 deepwater exploration rigs were also active.

The offshore oil-and-gas industry in the GOM has long depended on U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) Eurocopter H-65 Dolphin helicopter crews based in Corpus Christie and Houston, Texas, and New Orleans, La., but after 9/11 the USCG gained new border, port and homeland security responsibilities.

The tipping point for first-response helicopter support literally came in July 2005, when British Petroleum (BP) discovered that its $1-billion US Thunder Horse production platform was precariously listing 20 to 30 degrees and in danger of sinking, after being hit by Hurricane Dennis.

In August 2005, BP hired a hoist-equipped Sikorsky S-61N from Cougar for first-response support utilizing a NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) specialty air services operating certificate. This investment quickly proved its worth when Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita roared through the Gulf just weeks later, causing hundreds of millions of dollars of damage to offshore infrastructure.

In 2009, PHI Inc. introduced an S-76 C++ with a full, two-patient medical interior into the GOM charter market, billing customers for the full cost of each flight. (But this dedicated, 24-hour aircraft wouldn’t last long past the introduction of subscription-based contracts and newer hoist- and medically-equipped helicopters in the region.)

Later that year the delivery of a new S-92 to Cougar’s base at South Lafourche Leonard Miller Jr. Airport in Galliano, Louisiana, saw it immediately become the longest-range hoist-and-medically configured helicopter in the Gulf of Mexico. It soon proved its worth when Deepwater Horizon blew up on April 20, 2010, launching immediately to the BP Na Kika platform, some 14 miles southeast of Deepwater Horizon.

Once it reached Na Kika, the paramedic crew from Acadian’s Air Med Services that was on board teamed up with colleagues from an Acadian Air Med EC135 to set up a medical triage. Seventeen of the most badly injured Deepwater Horizon crew were then airlifted by USCG H-65s from the supply ship Damon B. Bankston and flown to the Na Kika.

The Cougar S-92 then flew six of the seriously injured workers to medical treatment in Mobile, Alabama, the Acadian EC135 flew two to a hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the rest were flown to medical facilities by USCG helicopters.

Around the same time, Era Helicopters introduced a subscriber-based first-response service, utilizing an AgustaWestland AW139 crewed by Era pilots, with Priority 1 Air Rescue providing the back-end hoist system operators, rescue swimmers and flight paramedics. The new service commenced in June 2010 from Port Fourchon, Louisiana, for launch customer Anadarko Petroleum Corp., providing SAR/emergency medical services (EMS) up to 200 miles offshore. A second AW139 SAR base opened at Galveston Airport when Shell signed up as Era’s second SAR/EMS customer, and then after Hurricane Isaac wiped out the roads to Fourchon in August 2012, the Louisiana AW139 relocated to Houma-Terrebonne Airport to take advantage of the better land access and instrument landing system.

In late 2010, VIH Cougar introduced its own subscription-based offshore helicopter EMS program, utilizing a pair of AW139s, later joined by an S-92, all equipped with medical interiors and crewed by Acadian paramedics (hoist capability was added later). VIHC clients include BP, Statoil, Anadarko and Shell.

Two other operators in the Gulf are also doing offshore first-response: Bristow does some ad hoc EMS for its clients there (unlike the dedicated SAR and EMS contracts it has around the world); while Chevron uses its fleet of some 30 helicopters to respond to its own emergencies.

Arctic Ocean

When the VIH Aviation Group bought Cougar in 2004, the VFR operator transferred a number of S-61Ns to Cougar for use on offshore first-response contract work. The S-61s initially flew on NAFTA specialty air service permits in the Gulf of Mexico during hurricane season, and on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill cleanup. They also supported 3-D seismic survey vessels working in the Arctic Ocean off Barrow, Alaska, beginning in 2005 and off Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, beginning in 2006.

First-response support was also provided to Cairn Energy’s two-year Arctic drilling program off Western Greenland in 2010-2011, from bases at Ilulissat and Nuuk. And, S-92s (supported by S-61Ns) were used there for crew changes and SAR standby.

Last summer, Cougar’s expertise was tapped by Chevron Canada to support a three-vessel seismic survey program in the Beaufort Sea. An AW139 provided SAR/EMS support from Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, to not only the survey vessels, but also the CHC Helicopters Canada Inc. AS332L Super Puma that was contracted for crew changes.

Meanwhile, in Alaska, Shell tapped VIH Cougar’s S-92 first-response expertise to support two Arctic drilling rigs — the Noble Discoverer in the Chukchi Sea and the Kulluk in the Beaufort Sea. The VIH Cougar S-92 was based on the Arctic coast in Barrow, and was also available to assist a pair of PHI S-92 crew-change helicopters operating to the rigs from Barrow and Deadhorse.

The Arctic drilling program — the first in the Chukchi Sea in 20 years — also saw the USCG deploy two Sikorsky MH-60 Jayhawks from Kodiak some 900 miles north of Barrow for the first time, to watch over the Shell drilling program and fly other SAR missions in the increasingly busy waters north of Alaska, including one mission where VIH Cougar provided top cover. Interestingly, the Jayhawks were not called into action on the rigs until two months after drilling ended, when 18 crewmembers from the Kulluk had to be rescued after the rig broke free from its tug during a storm in the Gulf of Alaska.

Moving drilling further offshore and into much deeper waters certainly has benefits, but of course it comes with a corresponding increase in safety and environmental risks. One new and hopefully effective tool to enhance the safety of the North American offshore oil-and-gas industry is the increasing array of dedicated commercial first-response helicopters that can be quickly dispatched to save lives.

Ken Swartz is an award-winning helicopter industry journalist who has covered the market for 35 years. He has spent most of his career as an international marketing and media relations manager with airlines and a leading commercial aircraft manufacturer. He runs Aeromedia Communications, a marketing and PR agency, and can be reached at kennethswartz@me.com.