The U.S. Army Hughes OH-6A light observation helicopter. Don Porter Collection Photo

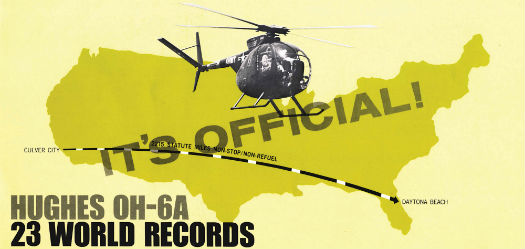

Imagine being alone in a light helicopter, making an overweight takeoff in the afternoon in California, flying nonstop through the evening and night without letting go of the controls, and landing on a beach in Florida the next morning. This dramatic flight took place April 6 to 7, 1966 — and was one of 23 world records a prototype Hughes OH-6A set that month. The Aircraft Division of Hughes Tool Company sponsored the attempt, which aimed to beat the nonstop distance record held by a Sikorsky SH-3A, a helicopter about 10 times heavier than the U.S. Army OH-6A, the progenitor of today’s MD 500.

Bob Ferry, Hughes’ 42-year-old chief test pilot, was at the controls of the OH-6A for the flight. A Korean War veteran who flew 90 missions in helicopters, Ferry served as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base from 1954 to 1960. “He flew everything at Edwards,” his wife, Marti Ferry, said. “He’d break the sound barrier one day and fly a helicopter the next.”

Ferry joined Hughes after retiring from the Air Force in 1964, and, just two years later, found himself in the cockpit of the OH-6A for the record flight.

For the attempt, the U.S. Army lent Hughes an OH-6A from its inventory. The airframe weight was minimized to gain more endurance, with duplicate flight controls, unused seats and even the door handles removed. The result was an unusually light 1,025 pounds (465 kilograms). To further minimize the aircraft’s weight during the flight, Ferry himself lost 20 pounds (nine kilograms). “My diet for one month prior to the flight excluded all fried foods and all starches and sugars, except that found naturally in fruits and vegetables,” Ferry wrote in his Hughes flight test report. To save a few more pounds, he wore knitted slippers instead of flying boots and an old leather flying cap rather than a flight helmet.

To boost fuel capacity, an aluminum tank that barely fit through the cargo compartment door was anchored to two-by-four sections of Douglas fir on the floor. On the left pilot seat, a rubber torso tank (named for its resemblance to a human torso) was strapped in, and, installed on the floor ahead of that tank, sat a two-foot-long oxygen tank.

The helicopter needed plenty of preparation — and so did its pilot.

“I established a sleep pattern starting five days before the flight by staying up until 2:00 a.m. each night and then arising at 10:00 a.m. the following morning,” Ferry wrote. “I think that this sleep schedule did much to sustain me during the trip. I did not take a sleeping pill the night before but I did get a good night’s sleep.

“During the few hours prior to [the] flight, I tried to minimize my activities to conserve energy. I kept my electrically heated jacket off for the departure because of the warm temperatures expected over the desert.” The jacket was used because it drained less power from the Allison T63-A-5A engine than extracting bleed air for cabin heating.

Fueled with 1,860 pounds (844 kilograms) of JP-5, the OH-6A weighed in at 3,235 pounds (1,467 kilograms) — more than three times its empty weight and an unusually high ratio of gross to empty weight for any shaft-driven helicopter.

The Army supplied a de Havilland CV-7 transport with long-range ferry tanks to serve as a chase plane and to certify the record. Aboard were Phil Cammack, the project engineer at Hughes who planned the flight, and crew chief Dick Lofland, who handled most everything else. An official from the National Aeronautic Association joined them to validate Ferry’s progress. The plan was also to have the airplane guide the helicopter across the country, as, to save weight, the OH-6A carried only a VHF transceiver. There was no radio navigation equipment.

The Day of the Flight

When the winds began to shift to the south, the original plan to land on a parking lot at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., was scrapped. The new destination was Miami, Fla.

After giving the ground crew a quick salute, Ferry made a hovering takeoff from the Hughes Airport runway in Culver City, Calif., at 2:20 p.m. on April 6. The machine staggered into the air, struggling for altitude. “[It] required 91 psi torque [over 300 shaft horsepower] to gain translational lift. I reduced power to red line limits as soon as I gathered climb ability,” Ferry reported.

Ferry said that he was challenged by the need to always keep the chase plane in view. “He took off after me and because of poor visibility and difficulty in spotting me as a small target, we did not meet for approximately one hour,” he wrote.

Hughes created a map depicting the route of the flight to celebrate the record. Don Porter Collection Image

With the overweight departure a success, the next challenge was to get through Banning Pass (now known as the San Gorgonio Pass). One of the deepest passes in the U.S., its mountains rise 9,000 feet along the sides. It’s also one of the windiest places in Southern California.

“I had to climb above 2,000 feet twice before getting through Banning Pass, but I was able to maintain 800 feet for much of the way to Blythe,” Ferry wrote. “I didn’t have a temperature gage, but the temperature was quite high.”

Flying low across the Mojave Desert and swinging southeast past Blythe into Arizona, the sun began to set while the terrain began to rise. “The air was mildly turbulent until sunset. This caused intermittent blade stall as a gust was encountered. The rotor speed would increase up to 108 percent during these gusts. Sometimes the gust would pull the collective pitch down even with a great deal of friction applied.”

The mountains encircling Tucson created another hazard. “It grew dark prior to arrival over Tucson and I had to climb to 4,500 feet. Soon I had to climb [to] 8,500 for terrain clearance.” The 452 miles (727 kilometers) from Culver City to Tucson took three hours and 48 minutes, averaging 118 mph (190 km/h).

Ferry had his hands full as the OH-6A crossed the southwestern states, climbing to 7,000 feet to scoot over the mountains ringing El Paso, Texas. The winds were generally light and variable but increased with altitude. The 265 miles (426 kilometers) between Tucson to El Paso took one hour and 55 minutes.

Climbing to higher altitudes, “I thought I might run out of oxygen, so I tried to conserve it by taking a deep breath and holding it. After a couple of hours of this, I got tired of it and concluded that I’d make it with ordinary breathing.

“I used 105 percent N-2 for the entire flight. I tried to use a lesser rpm but could not get the needed results for the weight-altitude combinations flown. When I was free of the mountainous area it was then desirable to go to a higher altitude to take advantage of the tail winds so that a high rpm was still called for.”

Flying on instruments wasn’t an option. “I had a backup attitude gyro installed in case it became necessary to depend entirely on instruments…but the instrument never gave a proper reading.”

And keeping warm at altitude wasn’t easy, either. “Putting on the electrically heated jacket, over my orange flying suit, took 20 or 30 minutes of determined effort. I discovered that the communication cords leading to my helmet were actually [tucked] under the jacket, pulling it way up in back, but I refused to go through the changing routine again.

“I kept warm except for the fingers. I had leather gloves with heavy wool inserts, but I found it necessary to put my hands, one at a time, under my arms inside the jacket for warmth.”

Crossing the expanse of Texas from El Paso to Waco was a long haul: 553 miles (890 kilometers). Ferry passed over Waco at 16,000 feet.

A marathon effort

With no autopilot installed, Ferry gripped the cyclic and collective during the entire flight. “It was necessary for me to fly the helicopter at all times. I could not trim it up for even a very short period.

“I drank one quart of fresh carrot juice during the flight and used no water, coffee or pep pills. I ate one tangelo, primarily to get it out of the way, since the map case was a little crowded. I did not get sleepy and did not feel fatigued.”

Traversing the 542 miles (872 kilometers) from Waco to Mobile, Ala., only took three hours and two minutes, as the OH-6A’s speed increased to 178 mph (286 km/h) owing to a tailwind and less of a fuel load. Ferry was at 24,000 feet now.

“As the night wore on, in order to fly to Miami, we had to cross the Gulf. We had a fuel flow meter, but at that stage I didn’t have enough confidence in it to fly over water. It wasn’t a good idea to come up a hundred miles short.”

Miami was scratched: The new destination was Daytona Beach. Ferry skirted the Gulf Coast shoreline passing over Mobile.

“The sun came up when I was east of Mobile and my chase plane flew right into it and I lost him for an hour. I finally saw him heading back to Tallahassee to refuel, and I was not to see him again.”

At a sizzling 185 mph (298 km/h) it took two hours to travel the 381 miles (613 kilometers) to Jacksonville, Fla., about 90 miles (145 kilometers) north of Daytona. Tail winds that averaged 75 knots helped. Ferry kept his eye on the dwindling fuel supply. Cammack recalled that when the ferry tank was almost empty, Ferry had to rock it from side to side to get all the fuel out.

“I continued east to Jacksonville to where I knew I had the record and I was sure of my position and then headed south along the coast,” wrote Ferry. “The strong crosswind started blowing me out to sea and I had to let down without delay. The collective was stuck in the cruise position and I had to use moderate force to lower it (the friction was off).

“When I was just three minutes past St. Augustine, I got a low fuel warning light and it then appeared that I could not make Daytona Beach. I pressed on and it became a question of guts versus discretion as to how I would go.

“I was sure that I could dead stick it in on the beach which looked good, but there was always the element of risk in hitting a submerged log or rock and damaging the ship so I landed at Ormond Beach with power.”

![]()

![]()

Bob Ferry in the cockpit, receiving a last minute briefing from Dick Lofland, crew chief for the flight. Don Porter Collection Photo

Exhausted after wringing every mile he could from the OH-6A, Ferry landed on the sand at Ormond at 8:28 a.m., 15 hours and eight minutes after he left Culver City. Eight of those hours were flown above 10,000 feet to take advantage of the tailwinds and burn less fuel. He averaged 150 mph (241 km/h) across the United States.

When Ferry climbed out of the helicopter, a boy asked him where he came from. Ferry said, “From California.” The boy responded, “In that?” Another beachgoer asked, “Where did you land last?” Nobody believed that Ferry had flown nonstop from the West Coast in such a small helicopter.

“Before the flight, Bob kidded the chase plane crew, ‘I’m going to run you guys out of gas,’ and he did,” said Cammack. “We had to quit and land in Tallahassee to refuel, while Bob went on to Ormond Beach.”

After the Army pilots landed the de Havilland CV-7 at the airport in Daytona, Cammack and Lofland hopped in a car and drove to Ormond. Finding the OH-6A shipshape, they measured the remaining fuel: there was about ten pounds (4.5 kilograms) left. The helicopter had averaged 8.5 miles per gallon.

After a sleepless night at home in California, Ferry’s wife Marti grabbed a ringing phone just before dawn. She was relieved to hear her husband’s voice: “Honey, I’m in Florida!”

Almost 50 years have elapsed since this iconic flight. The record stands as the longest unrefueled flight of any size or weight helicopter, covering 2,213 miles (3,561 kilometers) — which beat the previous record of 2,105 miles (3,388 kilometers) set by the Sikorsky machine in March 1965.

Following the flight, Bob Ferry continued his notable work at Hughes, recording the first flight of the AH-64 Apache, in September 1975.

He died in January 2009 at the age of 85.

Don Porter is the author of Howard’s Whirlybirds: Howard Hughes’ Amazing Pioneering Helicopter Exploits. At Hughes Helicopters, he was an OH-6A technical representative and later a project engineer on the AH-64 Apache program.

Great article! Small correction: The Pentagon is not in Washington, D.C. Only its mailing address is in the District.

It is across the Potomac River in Arlington, Virginia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pentagon.