Behind every operating helicopter is a skilled maintenance team.

Thousands of people are required to keep the North American fleet of about 10,000 civilian helicopters in the air, so they can serve customers and make money.

Many of these helicopters are so called legacy aircraft that are older than their flight and maintenance crews — especially in Canada. Other helicopters are at the opposite end of the spectrum, and embody the latest in leading edge technology.

Vertical spoke to maintenance directors and managers in the United States and Canada to get a snapshot of the current state of affairs in the commercial helicopter industry. The responses we received show what is “top of mind” for maintenance engineers, technicians, executives, and managers in North America today.

Archie Gray — Senior vice president of aviation services at Air Methods Corp.

Archie Gray — Senior vice president of aviation services at Air Methods Corp.Following a couple of high-profile acquisitions of major air tour operators, Air Methods now ranks as one of the largest commercial helicopter operators in the world (by fleet). All told, it has a fleet of 450 aircraft including about 400 helicopters from 300 bases across the entire United States — and maintenance personnel are located at almost all of these.

“To keep aircraft reliability high and direct operating costs down, Air Methods constantly monitors the reliability of every one of our aircraft and know the mean time between unscheduled removals [MTBUR] for every one of the components in every one of our aircraft,” said Archie Gray, the company’s senior vice president of aviation services.

“We also know exactly what we spend to maintain every single one of our aircraft. On HEMS [helicopter emergency medical services] missions, heat to the helicopter component is very detrimental — and takeoff cycles produce a lot of heat. Each HEMS mission typically lasts an hour and includes three legs — to the patient, to the hospital and back to base — which means we average three [engine] cycles per hour. We share our [MTBUR] data and cycle data with the OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] to try and reduce our maintenance costs.”

Gray said the company’s biggest challenge is recruiting qualified mechanics. “Aviation careers are not being promoted in the school system anymore, so there are not as many people choosing aviation as a career,” he said.

The company generally hires mechanics out of maintenance trade schools and puts them through an 18-month training program at one of its Part 145 maintenance facilities in Pittsburgh, Penn., or Denver, Colo. They will then be assigned to one of the Air Methods’ emergency medical services bases under supervision.

Gray said that these mechanics are entering an industry that’s undergoing a technological evolution.

“Today a mechanic approaches the helicopter for maintenance with a computer to download the maintenance manual, parts catalogue etc., and to investigate any fault codes from the diagnostic system, much the same way as they do with a car at a dealership,” he said. “We need well-rounded helicopter mechanics with more avionics and electrical experience to properly diagnose and interpret these systems in order to make the necessary changes and reset the systems.”

Air Methods has 40 helicopters equipped with the Appareo flight data monitoring (FDM) system and recently contracted to install the system in another 150 of its helicopters.

“With the addition of the 150 Appareo systems we will be able to have a more comprehensive safety system and [we] recently hired a FOQA [flight operations quality assurance] manager to expand our internal capabilities,” said Gray.

A few years ago, Air Methods introduced a safety management system (SMS) across the entire company — including the maintenance organization.

“SMS systems are extremely expensive to implement but every dollar we spend we get back in greater safety and reliability,” said Gray.

Kurt Koehnke — Vice president of maintenance at Columbia Helicopters

Kurt Koehnke — Vice president of maintenance at Columbia HelicoptersColumbia Helicopters is a commercial heavy-lift operator with aircraft on operations around the globe, including contracts in the U.S., Canada, Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea and Peru.

Kurt Koehnke, vice president of maintenance at Columbia, said the biggest change the company has seen in recent times was due to its expansion into Federal Aviation Regulations Part 135 operations in Afghanistan.

“Our historic business has been external load work using 16 [Columbia Vertol] 107 and six [Columbia] Model 234 helicopters for logging, firefighting and oil rig moves,” he said. “In Afghanistan, we’re operating four Model 107s and one 234 to fly passengers and internal cargo for the US military, which sees each helicopter flying at least 200 hours a month in harsh operating conditions.

“Launching passenger operations was more complex for us as the helicopters have full interiors and seating, heaters and air conditioning, and a different fuel system. Our utility aircraft have no interiors, so the inspections are much easier. The high operational tempo also means that about 90 percent of the maintenance is done at night.”

To ensure high availability across its fleet, Columbia has a large spare parts inventory in the field to support each of its helicopters. This includes spare engines, rotor blades, rotor heads and transmissions, as well as hundreds of line items.

“When you are moving a drilling rig in the jungle, a grounded helicopter can cost [a customer] tens of thousands of dollars a day,” said Koehnke.

Columbia bought the type certificates for the Model 107 and 234 from Boeing many years ago, and now holds the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) production certificate to build parts for both helicopters.

“Owning the Type Certificate adds an extra level of control that ensures reliability and helps drive down costs,” said Koehnke.

One of the more significant maintenance tools Columbia has introduced in the last half decade is the Honeywell VXP Optical Tracker, which provides blade track and lead/lag automatically.

“We used to use the old Chadwick tracking system which was very time consuming,” says Koehnke. “When we introduced the [Honeywell] VXP system, we found that the software algorithms allowed us to do the adjustments to the blade track and lead/lag at once in a fraction of the time.

“Some of our pilots have 20,000 flight hours on our helicopters and they are the best ‘accelerometers’ we have. They say that with this system we’ve been able to achieve the lowest vibration levels they’ve ever experienced in a Model 107 and 234 helicopter.”

Morris Forchuk — Director of maintenance at Helijet International

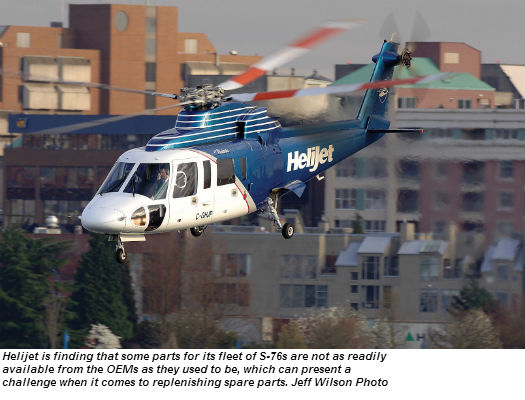

Morris Forchuk — Director of maintenance at Helijet InternationalHelijet International, based in Vancouver, B.C., flies 17 helicopters — including 11 Sikorsky S-76s — for scheduled passenger, EMS and charter services.

Morris Forchuk, director of maintenance at Helijet, explained how the company keeps aircraft reliability high and direct operating costs down. “We work with our suppliers and build relationships with suppliers across the overhaul and repair industry,” he said. “We also obtain extensions to our TBOs [time between overhauls] for all our aircraft, including the S-76s, operating on regular scheduled passenger services.”

Forchuk said the biggest challenge the company faces was in the level of OEM support. “We have noticed a gradual trend in the reduction of technical support and our ability to get parts,” he said. “Historically, getting parts was relatively easy because OEMs carried an inventory that would allow us to replenish our inventory. Now, items that require regular replacement are no longer readily available.”

When it comes to new technology, Forchuk said keeping pace with the speed of change was a challenge in itself. “We put a new Garmin GPS system into our S-76s five years ago, but our retrofitted system is no longer supported by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and replacement systems have different dimensions and are not “plug and play” — so require a new STC [supplemental type certificate].

“Updating avionics in older aircraft is a challenge, as is knowing exactly how to address the problem. Universal pooling of different MRO databases to help find a reliable outside system repair agency would be very helpful and we would consider participating in a pooled information system if it was available.”

When it comes to recruiting new talent, Forchuk said a lot of those coming into the industry want to live in the city year-round. “That’s a challenge because Helijet has up to six S-76s flying guests into sports fishing camps on the B.C. coast from May through September, and we need AMEs [aircraft maintenance engineers] who can work two-week rotations up north.”

Scott Churchill — President and director of maintenance at Scott’s Helicopter Services

Scott Churchill — President and director of maintenance at Scott’s Helicopter ServicesScott’s Helicopter Services of Le Sueur, Minn., operates 19 Bell 47s, 12 of which are turbine-powered Soloy-Bell models. The company also flies seven Bell 206B JetRangers and a Bell UH-1 Huey for utility work.

The Bell 47 by definition is older technology, but helicopters working in the agriculture industry are being outfitted with advanced GPS navigation systems and modern spray systems.

“To keep operating costs down we do a lot of preventative maintenance,” said Scott Churchill, president and director of maintenance at Scott’s. “Agricultural flying is brutal on aircraft because you’re landing and taking off every couple minutes, operating at high gross weights and working with various chemicals. We try to do maintenance in the pre-season and we divide large maintenance jobs into two parts to reduce downtimes.”

Churchill said that when parts for the Bell 47 started to become scarce, he bought a PMA parts company for “selfish reasons” because he needed the parts to keep his fleet going.

He bought the type certificate for the Bell 47 family in 2009, and is now putting the helicopter back into production as the Rolls Royce RR300-powered Scotts-Bell 47GT6 turbine.

Commenting on the helicopter maintenance industry in general, Churchill said the biggest change he’s seen is the increased emphasis on the training of entry level mechanics.

“There is a lot more specialized training to understand avionics, electronics and composite structures,” he said, “and a lot more emphasis on record keeping to ensure there is a paper trail — either because of traceability or litigation.”

Terry Hutchings — Maintenance manager at Universal Helicopters

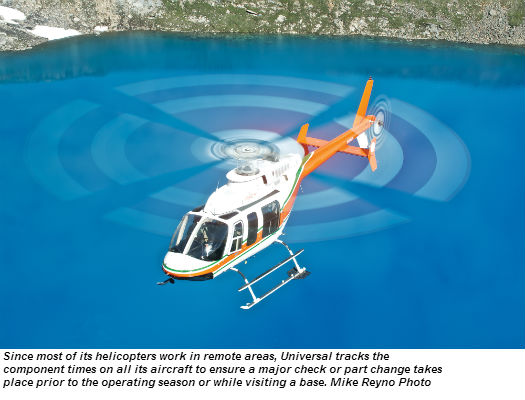

Terry Hutchings — Maintenance manager at Universal HelicoptersUniversal Helicopters operates a fleet of 19 single-engine Bell and Airbus Helicopters aircraft from four fixed bases in Newfoundland and Labrador, with about 80 percent of company flying taking place between April and October. The company’s operations take it throughout the eastern province and “as far north as you can go in the Arctic,” according to Terry Hutchings, Universal’s director of maintenance.

“One of the challenges we have working in a remote region is that all the parts for our helicopters have to come by air freight,” said Hutchings. “In addition to air freight costs, we have to pay additional fuel and Nav Canada surcharges on every parts shipment. This can really add up if the helicopter manufacturer doesn’t have enough inventory on the shelf and ships our order in three lots.”

All of Universal’s helicopters are equipped with the SkyTrac satellite-based flight following and two-way voice communication system. One of the company’s Airbus Helicopters AS350 B2s has been upgraded to have flight operation quality assurance / flight data monitoring capability.

“We will use this test aircraft to record engine parameters but we still need to decide how we are going to manage all the new data we collect,” said Hutchings.

Since most of its helicopters work in remote areas, Universal tracks the component times on all its aircraft to ensure a major check or part change takes place prior to the operating season or while visiting a base.

Universal has hired about 95 percent of its maintenance staff from the AME program at the Gander Campus of the College of the North Atlantic.

“The school puts out a good bunch of graduates who are very practical and familiar with our kind of work,” said Hutchings. “Not everyone wants to work away from home, outside, and under harsh conditions. We generally try to hire people who are from the north.”

Kelley Brandt — Director of maintenance at Bristow Academy

Kelley Brandt — Director of maintenance at Bristow AcademyBristow Academy operates a fleet of about 70 helicopters maintained by 40 maintenance technicians at campuses located in Florida, Louisiana and Nevada. The schools operate under FAR Part 141 rules and the maintenance is performed at the academy’s Part 145 Repair Station.

The workhorse of the fleet is the Schweizer/Sikorsky SH300CBi, which is supplemented by a fleet of Robinson R22s, R44s and Bell 206 JetRangers.

With a large number of students training to receive FAA, European Aviation Safety Agency and military pilot licenses, the goal of the maintenance staff is to ensure enough helicopters are available to meet training requirements that can see the fleet flying an average 2,500 hours per month.

“We train our own mechanics,” said Kelley Brandt, director of maintenance at Bristow Academy, who began her maintenance career working on heavy jets in Ireland. “We have an apprenticeship program on campus in Florida to train A&P [airframe and powerplant] mechanics. Training begins with an introduction to Bristow’s safety culture and core values and then students train through OJT [on the job training] for 18 months each before testing for their airframe and powerplant licenses.

“It’s an exciting time for the training world right now with the introduction of new and modern purpose-built training aircraft to the market,” Brandt continued. “When researching future aircraft we have to consider the manufacturers’ ability to support the aircraft when it comes to parts availability and technical support.”

Brandt said the biggest change she’s seen company-wide at Bristow in recent years is a cultural shift. “It’s not so much in the maintenance we’re performing, but in how we’re performing the maintenance.”

Brandt said new initiatives, including operational excellence and a safety management system, have given more focus to how the company is operating. On the shop floor, this has seen the introduction of continuous airworthiness surveillance systems on the Part 135 side of the company, operations being standardized, and the fleet consolidated to reduce the number of aircraft requiring inventory. “In parallel we’re also tracking the life of parts in more detail and analyzing reliability trends,” said Brandt.