Among airborne law enforcement units, “multi-mission” has long been a buzzword. Although some units have retained their traditional focus on patrol and surveillance, law enforcement aviation is no longer so narrowly defined; today, it’s not uncommon to see a police helicopter conducting a rescue mission or firefighting with a Bambi Bucket when the occasion demands.

Such versatility can be a boon for the communities those units serve. In these tough economic times, it can also be the key to an airborne law enforcement unit’s survival. Like a well-diversified business, a multi-mission aviation unit has a better chance of weathering a recession intact, because it offers more of the services its customers — the taxpayers — require.

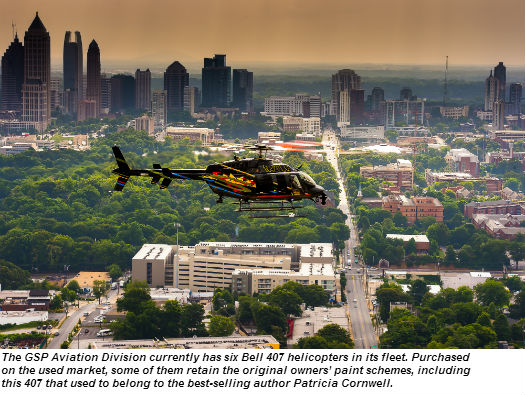

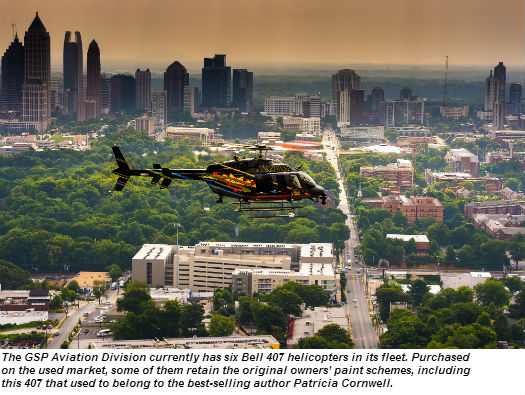

Few airborne law enforcement agencies, however, have embraced the multi-mission vision as thoroughly and successfully as has the Georgia State Patrol (GSP) Aviation Division. Over the course of four decades of operation, the GSP Aviation Division has done a remarkable job of expanding the services it offers to public safety agencies in Georgia’s 159 counties, all of which can call on the unit for aerial support. From search and rescue to firefighting, from marijuana interdiction to disaster response, the division conducts an impressive variety of missions with its 12 Bell helicopters, guided by the philosophy, according to aviation director Capt. G.A. Mercier, that “if the aircraft can do it, we need to be able to do it.”

Not only has this approach delivered real benefits for the citizens of Georgia, it has been good for the unit itself. While other airborne law enforcement units were selling aircraft and slashing flight hours in the wake of the global financial crisis, the GSP Aviation Division was actually expanding, backed by exceptionally strong public and institutional support. Certainly, the division is far from being able to spend freely. But smart decisions about how to allocate its resources have allowed it to maintain a high tempo of operations, without sacrificing safety or training.

According to Mercier, the GSP Aviation Division’s success is all about demonstrating value. Whether it’s local sheriffs or state officials witnessing the unit at work, “I tell my pilots, you need to convince these people that they can’t live without you,” he said. “If I find a missing child or an Alzheimer’s patient who couldn’t be found [from the ground], how do you put a price on that? . . . If you provide the services that those people can’t live without, it’s a little harder to cut them.”

A 40-Year Tradition

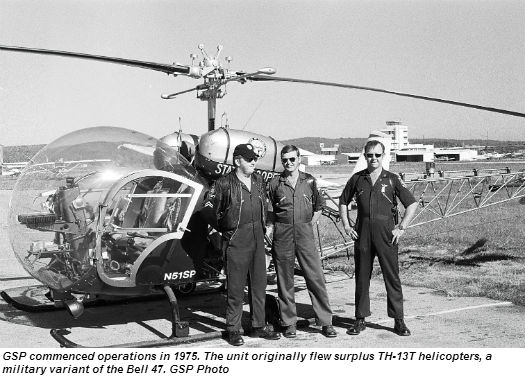

The GSP Aviation Division began organizing in the early 1970s, commencing operations in 1975 with one lieutenant and three pilots. Its first aircraft were military surplus TH-13T helicopters — military trainers based on the Bell 47 — and a T-41 airplane, a variant of the Cessna 172. The unit was originally based at Fulton County Airport/Charlie Brown Field in Atlanta, and retained its headquarters there until 1995, when it relocated to Cobb County Airport/McCollum Field, about 25 miles northwest of downtown Atlanta.

Like many early airborne law enforcement units, the GSP Aviation Division initially focused on traffic enforcement and surveillance. However, it was also a pioneer in a mission that remains important to it today — marijuana interdiction. The unit began its marijuana interdiction program in the late 1970s, at first concentrating its efforts in the North Georgia mountains, then gradually expanding throughout the state. In 1983, the unit was recognized with Helicopter Association International’s Law Enforcement Award for its innovative use of rotorcraft in what was then widely known as the “war on drugs.”

Of course, time has shown that the war on drugs is not easily won. The marijuana trade continues to flourish in Georgia’s humid subtropical climate, with a recent increase in the number and size of marijuana grows on public lands posing a particular threat to the environment and public safety. So the GSP Aviation Division continues to keep pressure on marijuana growers, with six military surplus Bell OH-58 helicopters currently dedicated to the marijuana interdiction mission. In 2013, the unit flew approximately 1,000 hours in support of the Governor’s Task Force for Marijuana Suppression, resulting in the eradication of more than 6,000 plants worth an estimated $12 million.

As significant as these efforts remain, however, the GSP Aviation Division has diversified greatly since its early years. The first major leap in its capabilities came in the 1980s, when the unit moved out of Bell 47s and into larger, more versatile Bell 206 JetRangers. Then, in 1997, the unit acquired its first Bell 407 — a model that had the power and tail rotor authority to conduct more missions safely. “We saw the need for it,” explained Mercier, who has been with the unit since 1993. “We were asking pilots to do so much with the Bell 206s. . . . They were operating all the time at the limits.”

Not only did the introduction of the 407 improve the safety of existing operations, it allowed the unit to take on new missions, including short-haul rescue, and firefighting in support of the Georgia Forestry Commission. The addition of two surplus Bell UH-1H helicopters — one of which was equipped with a hoist — further expanded its rescue and firefighting capabilities. The unit also began providing support to the State of Georgia SWAT Team with its 407 and UH-1H helicopters, developing programs for fast-rope, rappel, and aerial shooting operations.

As the unit’s aircraft were becoming more capable, so, too, was the technology those aircraft were equipped with. The introduction of more advanced forward-looking infrared (FLIR) cameras in the early 1990s dramatically boosted the unit’s search capabilities, as did its adoption of night vision goggles (NVGs) around 1995. Both developments arrived in time to benefit the unit during the 1996 Olympics — a watershed event for the division. “Prior to that time we really hadn’t had a lot of large events that we had worked,” noted Mercier. “During the Olympics we worked out of this hangar 24/7 . . . it was nonstop, crazy.”

Since that time, the GSP Aviation Division has further enhanced its incident management capabilities through the introduction of microwave downlinking: the ability to transmit real-time video to commanders on the ground. The unit now plays a major role not only in aerial support for major events such as the 2004 G8 summit in Sea Island, Ga., but also in coordinating the aviation response to natural disasters including hurricanes and tornadoes. Throughout this process, it has developed strong working relationships with a range of local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, as well as the Georgia National Guard and the Department of Defense.

The GSP Aviation Division’s steady advance in aircraft and capabilities didn’t always occur systematically, however. According to Georgia Department of Public Safety Commissioner Col. Mark McDonough — who spent about a year assigned to the division earlier in his career — the unit’s aircraft acquisitions were historically driven by price and opportunity, rather than a master plan. This resulted in something of a “Gypsy caravan” — a mixed fleet that became increasingly costly to train in and maintain.

To streamline its maintenance and training costs, GSP elected several years ago to standardize its primary fleet by replacing its remaining JetRangers with 407s purchased on the used market (although it retained one 206 for training purposes, in addition to the OH-58s it uses for marijuana interdiction). Earlier this year, the unit also returned its aging UH-1H Hueys to the U.S. government, with the intention of replacing them with one modern, twin-engine helicopter, such as a Bell 429.

“We were spending an inordinate amount of maintenance time and training on aircraft that were rarely used,” McDonough said of the decision to return the Hueys. With the expected acquisition of the twin-engine helicopter later this year, he said, “We’ll have all of that capability in one new aircraft under warranty.”

Statewide Coverage

The GSP Aviation Division’s headquarters building in Kennesaw includes administrative offices; a kitchen and bedrooms for any personnel who may be working overnight; and the division’s maintenance facilities, including a large maintenance hangar, clean room, and parts and records rooms. According to director of maintenance Jeff Gehrlich, a civilian who has been with the unit for 18 years, he and the five members of his team conduct almost all of their maintenance out of Kennesaw, where they work a typical Monday-through-Friday schedule. Simply keeping up with the unit’s 12 helicopters and one Cessna 182 airplane, which collectively log around 3,500 flight hours per year, is a feat in itself.

“It’s a little tough keeping all these things in the air,” said Gehrlich. “Those aircraft are out flying every week. . . . The biggest challenge is just trying to work the maintenance schedule around the flight schedule.”

While the division’s maintenance is centralized, however, flight operations are not. To provide adequate coverage for Georgia’s 59,425 square miles (153,909 square kilometers), the division maintains five field hangars strategically located throughout the state, in Albany, Gainesville, Perry, Reidsville, and Augusta. At night, there are two helicopters on call — one responsible for the north half of the state, and one for the south. This arrangement allows the division to provide round-the-clock, statewide coverage, while keeping staffing relatively lean, at just 14 pilots. In an effort to minimize fatigue, pilots work varying shifts. During one 28-day period, they’ll work 12-hour night shifts for seven days on, seven days off, but after that they’ll have a period of eight-hour shifts with variable days off, followed by 28 days of normal weekday shifts.

New pilots are brought into the unit as required, typically a couple of them every few years. The position is sworn, and troopers must spend at least three years on street patrol before being eligible for the Aviation Division. To be considered for pilot positions, they must also hold at least a commercial pilot certificate with either an airplane or rotorcraft category rating, demonstrating their personal commitment to and aptitude for aviation. After their selection, pilots receive whatever additional training they require from the unit’s in-house certified flight instructors (there are currently seven on staff), and are then assigned to the marijuana interdiction program, where they fly with another, more experienced pilot until accumulating 500 flight hours.

According to Mercier, the “low and slow” flying experience that these new pilots gain on interdiction missions helps them develop their skills rapidly, while supervision from another pilot keeps them safe. “At the end of it, their proficiency level is really high,” he said. Pilots will then undergo an extensive, in-house NVG training program designed to prepare them for general law enforcement operations, followed by training for special missions as they progress through their careers. Throughout, they’ll also receive regular recurrent training, including twice-yearly training in emergency procedures from Bell Helicopter instructors. “If you don’t have the training you need and you don’t have the currency you need, you’re setting yourself up for disaster,” said Mercier, noting that he has never had a problem in obtaining funding for training. “I haven’t had to fight for it at all — I’ve just had to explain the importance of it.”

That’s not to say that the GSP Aviation Division is wholly without budget constraints, only that training is one of its top priorities. The unit is always mindful of costs and saves where it can; for example, many of its new used Bell 407s are in their original owners’ paint schemes, to save the cost of repainting them. The unit has also economized through its tactical flight officer (TFO) program, which, rather than employing full-time TFOs within the Aviation Division, uses troopers and members of other law enforcement agencies who are detached to the division. According to lead TFO Sgt. Steve Mickels, a member of the Hall County Sheriff’s Office who is the only full-time TFO assigned to the Aviation Division, a side benefit of this arrangement has been strengthened relationships between the unit and the local law enforcement agencies that lend it their personnel. “The relationship between the State Patrol and the individual agencies . . . [is] an example of what can be done with limited resources,” he said.

Of course, not having full-time TFOs also comes with significant drawbacks, which the unit has worked hard to overcome. Several years ago, Mickels recognized that the increasing sophistication of FLIR cameras and other mission equipment demanded more formal training requirements, so he spearheaded the development of a 40-hour course designed to give new TFOs a solid grounding in these systems. Even so, Mickels acknowledged, there’s no substitute for practice. “The more you fly, the more experience you gather, and the more proficient you become,” he said, explaining that the division hopes to bring on more full-time TFOs in the near future.

Just as the unit as a whole has diversified its capabilities over the years, the TFO role also continues to expand. In addition to operating camera equipment during law enforcement and search missions, TFOs serve as crew chiefs during short-haul rescues, and perform other duties as circumstances demand. Now, TFOs are receiving additional training in how to assist pilots during emergencies, with basic flight training for TFOs a possibility in the future. As Mickels observed, “It’s always good to have two crewmembers who can fly the aircraft.”

Keeping Things Safe

Aircraft, equipment, and capabilities aren’t the only things that have evolved over the GSP Aviation Division’s four decades of operation — the mindset of its personnel has changed, too. “The industry trend has gone a totally different way than it used to be,” observed pilot Cpl. Tony Hightower, recalling that members of the unit used to take to the air in t-shirts and tennis shoes rather than Nomex flight suits. Now, he said, the unit has become more professional not only in its appearance, but in its entire approach to operations. Col. Mark McDonough echoed these remarks. “I think there [used to be] a culture of pilot shopping; I experienced it when I was in the unit 14 years ago,” he said. “I think a lot of time risks were taken that shouldn’t have been.”

A key milestone in the division’s evolution toward better, safer operations was the 2012 adoption of a Safety Management System, making the division one of the first law enforcement aviation units in the country to embrace SMS. The program requires a proactive approach to identifying hazards, implementing risk management, encouraging employee participation, and requiring timely feedback. “It’s been a very educational tool for us,” said Hightower, noting that SMS has resulted in a number of positive changes at the division — from simple procedural changes related to checklists, to a serious examination of the far-reaching effects of pilot fatigue. “The biggest factor we ran into after we started compiling data and reports was the fatigue issue . . . 96 percent of our high-risk scores were related to fatigue.” In response, he said, the unit modified pilots’ schedules and took other steps to address the problem.

SMS has also proved to be of value of the maintenance side of the house, said Jeff Gehrlich. Although the unit would ideally prefer to standardize the cockpit layouts of its Bell 407s, buying them one at a time on the used market has put constraints on its ability to do so. Even so, information gathered through SMS helped Gehrlich improve upon the cockpit layout of the latest aircraft, making it more user-friendly for pilots and TFOs.

As the unit has moved toward ever-higher levels of professionalism, however, it hasn’t sacrificed the strong sense of camaraderie that unites its personnel. “This whole unit since I’ve been here is like a family,” said Gehrlich, claiming that, in the more than 18 years that he has been with the unit, he has never really had a bad day. According to Gehrlich, a shared sense of pride and accomplishment permeates the division; when a flight crew tracks down a bad guy, rescues an injured hiker, or returns a lost child to her family, everyone at the unit feels good about the success.

“That’s what these guys do — they bring people home to their families,” said McDonough. “What’s the value of one life? If it’s your relative, you’ll do whatever it takes.” For the past 40 years, the citizens of Georgia have agreed, providing the GSP Aviation Division with the support it needs to provide the services they can’t live without.