London bustles. A major financial, cultural, and political center, the UK’s capital is a truly global city, with an estimated 10 million people living, working, or traveling within its borders. Throughout the day, its famous roads and winding passageways, heaving transport network, and iconic landmarks are buzzing with activity; while its world renowned nightlife carries the city’s energy into the small hours with after-dark revelry.

Each and every day, a small group of these people — whether it be a commuter in busy traffic, a tourist looking the wrong way before stepping out onto a crossing, or someone who gets into a disagreement with the wrong person in a pub — will suffer such a severe trauma injury that their ability to survive the length of even a short ambulance journey to a hospital is questionable. It is for these patients, in their moment of greatest need, that the doctors, paramedics, and pilots of London’s Air Ambulance will effectively bring the emergency department from the hospital to the roadside, performing lifesaving (and often groundbreaking) operations in some of the most challenging environments. For these highly skilled medics, the city of London is their hospital.

But the story of London’s Air Ambulance is not just the story of the medical capabilities the service delivers; it’s the story of how a small, dedicated team of driven individuals fought to establish a reputation and support for pre-hospital medicine amongst a medical community that originally viewed helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) with great suspicion. And it’s the story of how this world-class service has ambitions to change the perception and delivery of HEMS well beyond its own city or national borders.

Putting it into practice

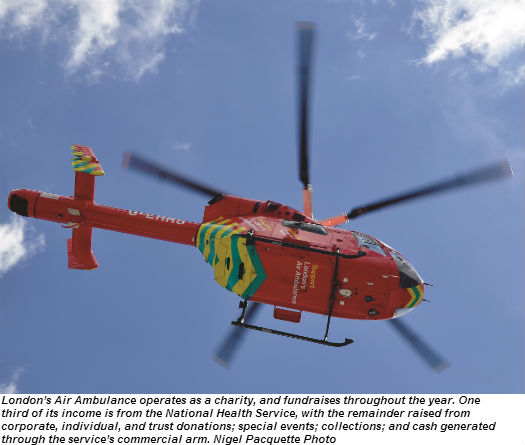

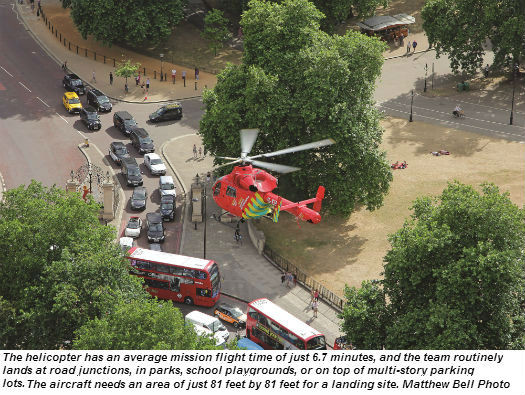

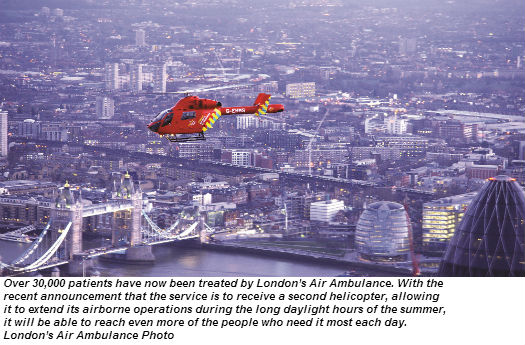

During the day, the service operates a single MD Helicopters MD902, with its NOTAR (no tail rotor) antitorque system and high main rotor deemed most suitable for the dense urban environment in which London’s Air Ambulance must operate. On board each flight are two pilots, a doctor, and a paramedic — along with a vast range of cutting edge medical equipment and technology. Based fairly centrally at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, the helicopter is able to reach even the furthest parts of its 600-square-mile service area within 11 minutes — although the crew’s average flight time is just 6.7 minutes.

It’s a common misconception among the public that London’s Air Ambulance carries patients; while it has the capability, it only does so about 10 percent of the time. Primarily, the aircraft is used as a medical team/equipment delivery platform.

At night, or during adverse weather conditions, the service switches its method of delivery to two specially-configured high performance Skoda Octavia automobiles. This enables the service to ensure round-the-clock coverage for the city.

On any given day, the London Ambulance Service (responsible for the city’s medical first response needs) receives about 5,000 calls for help. Of these, London’s Air Ambulance will be dispatched to, on average, just six. The aircraft will attend about half of these calls.

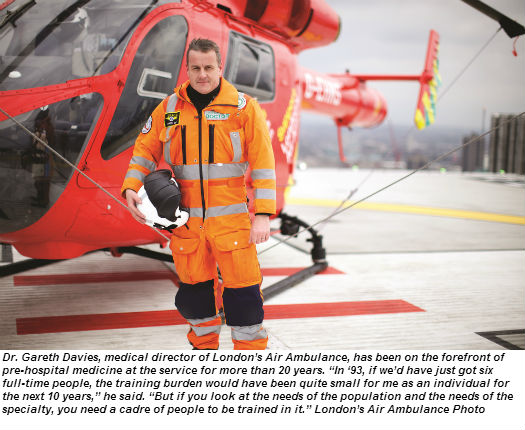

“There aren’t that many patients, but they’re all seriously injured, so they’re all be in the dying process,” Dr. Gareth Davies, the service’s medical director, told Vertical 911. “They’re likely to die in the early phases of their injury — either at the scene, en route [to the hospital], or at hospital.”

Although the cause of such severe injuries can vary widely, they’re most commonly the result of falls from height, road traffic incidents, and penetrating trauma (shootings or stabbings). The service aims to reduce the gap between the injury and definitive hospital care by bringing everything that’s at the hospital to the patient’s side — instantly creating an operating room, an intensive care unit, or resuscitation room with the appropriate drugs, equipment, or fluids.

Many of the procedures and techniques used by the medics have been pioneered by the service. It was the first in the UK to carry blood and administer blood transfusions, to carry drugs that can manipulate coagulation, and to administer pre-hospital anesthesia. In terms of surgical procedures, it was the first in the world to perform pre-hospital thoracotomy (open heart surgery) and thoracostomy (draining the chest cavity to allow the lungs to breathe). Davies said that the survival rate for the patients that require a thoracotomy is nearly 20 percent — a success rate he said was unheard of in emergency medicine. “Open heart surgery was, of course, being performed by cardiac surgeons up and down the country, but had never been done in a pub, or at a roadside,” he said. “It’s a big procedure; no one should underestimate that opening someone’s chest in the street is a big event, and our challenge was to make sure that we could do that and do it reproducibly with good results.”

Such interventions are certainly not taken lightly — they’re mandated by the situations the advanced trauma teams face. Open heart surgery is only performed if the patient is about to lose their life, or is already in arrest. “If you can do an operation in a hospital, you should do it in a hospital,” said Davies. “You should only do an operation in a pub when you’re not going to leave the pub without it. . . . What we do is what’s right for that individual patient and that patient’s specific set of injuries. If you’ve been stabbed in the abdomen and you’re bleeding from a liver laceration, there is no point in spending 30 minutes onscene giving someone a blood transfusion, when the resolution of that problem is to get to hospital and have a surgeon pack your liver. In those patients, we will compress the scene down as tightly as possible, do very little, and get moving.”

This nuanced care changes not only the definitive live/die outcome, but also the long-term prospects of survivors, minimizing the impact of injuries that might otherwise have caused lasting and significant disability.

However, Davies is well aware that the methods employed by London’s Air Ambulance have their critics —with there being a disparity of views in some places as to whether such advanced medicine at the scene was beneficial.

“The North American systems grew up for many years producing data that [said] advanced life support at the scene was potentially dangerous and killing patients,” he said. “But increasingly, people are looking and going, ‘We should take a closer look at what they’re doing in the UK — or in Europe. Because it’s producing survivors that don’t survive anywhere else in the world.’ ”

Charitable beginnings

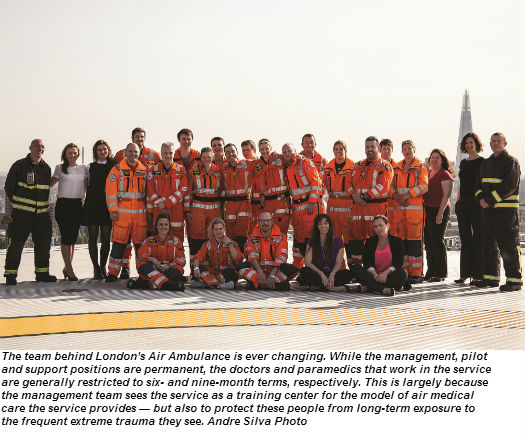

There are many remarkable things about London’s Air Ambulance — not the least of which is the way it’s funded. It is, in fact, a charity, operating in partnership with both Barts Health NHS Trust (which provides advanced trauma doctors for the service, as well as direct financial support), and London Ambulance Service (which provides paramedics, and hosts the organization’s dispatch service). In addition to this National Health Service funding, the charity fundraises throughout the year, and also receives support through corporate and individual donations.

The roots of the service lie in the fallout from a damning report by the Royal College of Surgeons about the lack of an organized trauma system in the city — and a campaign from the Daily Express newspaper, led by two London surgeons, for a medical helicopter.

Getting the helicopter (initially an Aérospatiale AS365 N Dauphin) — and creating the infrastructure at the hospital to support it — was the relatively simple part. Recruiting the doctors to work on the service proved to be the challenge.

“No one knew what the job meant, whether it would do your career good or do your career harm,” said Davies. There was friction between the air ambulance and local hospitals and doctors when the service began, as there was a general feeling that helicopters took patients from other hospitals, denuding them of both patients and expertise.

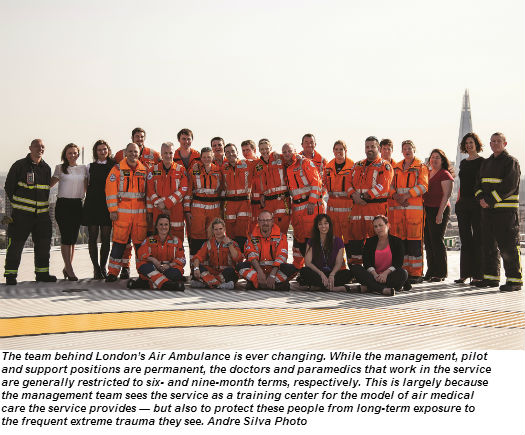

However, Davies was one of the doctors that joined the air ambulance in its infancy, and after a couple of years as a junior flight physician, was appointed the consultant responsible for the service – a role he now shares with three others. Part of his remit on his appointment was to change the perception of pre-hospital care, and create an appropriate training scheme for doctors entering the field, which would not only improve the care the team could deliver on the streets, but also increase the field’s credibility. Rather than just focus their efforts on training a handful of full-time doctors to work on the service, however, Davies and the London’s Air Ambulance team decided to instead create six-month postings — and accept the resulting heavy and continuous training burden. They hoped that when doctors left the service, they would be convinced of the suitability of the doctor/paramedic model used in London, and spread it to other services.

“We decided that the needs of the specialty were paramount,” said Davies. “There’s no point just having one helicopter in London that’s really good, and no-where else — no other helicopters with doctors on them. The only way was to sort of create this mass of individuals that were hopefully well trained, hopefully experienced, and hopefully passionate like we were about this sort of care.”

The caliber of the doctors that now apply to work at London’s Air Ambulance — and the fact that they come from all over the world to do so — suggests that the medical community’s perception of the model has changed quite dramatically since the service’s early years. Most doctors have already completed seven or eight years of practice by the time they arrive (after having passed a screening interview), and a good proportion of them are already consultants. They then go through an intensive peer-reviewed training month where they’re taken through every facet of the organization, before a day of testing with a consultant. It’s this level of expertise that the service is bringing each day to the most seriously injured people in London.

“To have a five- or six-year medical degree, then spend another seven years practicing, and then be treated by that individual as you’re dying, we felt was appropriate,” said Davies. “That’s the best society could chuck at you.”

In the cockpit

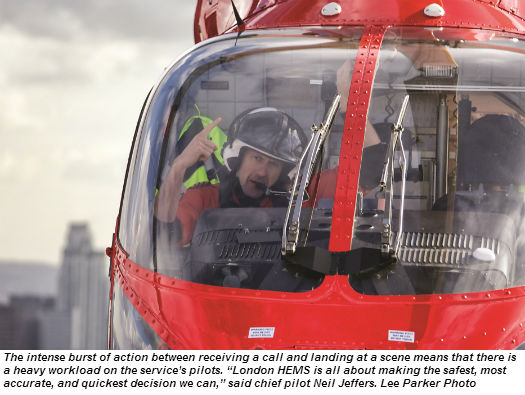

It’s hard to imagine a more intense workload during a flight than that taken on by the five full-time pilots at London’s Air Ambulance. The airspace in which they operate is some of the busiest airspace in the world. The nature of the role and the sheer volume of information to process requires the service to fly dual pilot. Flying at about 130 knots, and between 500 to 1,000 feet above ground level (AGL), flights can be as short as just two minutes, during which time the crew will have spoken to air traffic control and ambulance control, located the exact position of the patient on a London A-Z map book, identified a potential landing zone nearby, completed the landing checks, and touched down.

The aircraft needs a landing zone of about 80 feet by 80 feet (twice the length of the aircraft from rotor tip to tail). In the dense urban London environment, school playgrounds are good candidates (the team carries bolt cutters in case they find themselves fenced in), while box junctions, tops of multistory parking lots and even bridges are also common destinations.

Four of the pilots are qualified to fly as captains, and although the service does perform line training to promote co-pilots to captains, they also hire direct-entry captains, dependent on experience. Co-pilots generally arrive with about 2,000 flight hours, while direct-entry captains have at least 3,000 rotary-wing hours.

At the scene, one pilot stays with the aircraft, while the other helps the medical team where they can, reinforcing the ethic of teamwork that runs through the service. “I think that I would be upset if a pilot came here just to fly,” said Neil Jeffers, London’s Air Ambulance’s chief pilot. “I think you’ve got to be interested in medicine. . . . One of the pilots has been here 13 years; he’s seen more trauma than any doctor will ever see.”

Currently, the crews fly 12 hour shifts — the maximum permitted — from 7:20 a.m. to 7:20 p.m. (light permitting). The recently-announced addition of a second helicopter will likely add another seven or eight freelance copilots to the team, and allow the charity to run two shifts a day during the long daylight hours of London’s summer months.

Making the right call

Paramedics complete the London’s Air Ambulance flight crews. Like the doctors at the service, they are only with the organization for a short period of time (for nine months rather than six), and they are all seconded from the London Ambulance Service.

Graham Chalk, London Air Ambulance’s lead paramedic and clinical liaison officer, told Vertical 911 that each one has at least five years’ experience, but they are mainly selected for their ability to deal with challenging situations, communication, and problem solving under pressure. “Because those things are often innate and difficult to teach,” he said.

The paramedic’s role is split into two; half their time with London’s Air Ambulance will be spent attending scene calls, while the remainder will be working directly in the London Ambulance Service’s dispatch center.

When attending a call, paramedics bring their knowledge of how to run a scene, working alongside the doctor to utilize their strengths and experience with things like working with other agencies or in hazardous areas — but they also do the exact same training at service as the doctors. “I see them intrinsically as the medical team,” said Chalk. “They both bring elements of clinical care to whatever they get to. . . . It’s a relationship based on each of their weaknesses and each of their strengths.”

HEMS Profile

In terms of the paramedic’s work at the dispatch center, their task is to make sure that the air ambulance’s one resource gets to the right seven or eight calls from those 5,000 that are received each day.

“It doesn’t matter how good you are unless you get to the right call quickly enough; all your medicine is worth nothing because they’ve either died already or you’re in the wrong place,” said Chalk. “If you have one resource, overtriage is pointless, because if you’re spending your time flying out to everything that sounds a bit bad, then you’re not going to be available to the one that genuinely is. So it’s about not sending as much as it is sending. . . . I think it’s a real art.”

Chalk said the service has a 70 percent dispatch accuracy rate (when they’re reaching the best candidates for their help) — with the remaining 30 percent including patients already beyond aid, or responses considered overtriage.

The paramedics’ secondment is restricted to nine months largely it allows London’s Air Ambulance to train as many as possible in the very advanced trauma care they perform. But there’s also an element of protecting the paramedics from the nature of the role.

“The average paramedic in London will see probably one maybe two serious traumas in a year — extremely sick patients with multiple injuries — whereas we’re seeing probably three or four a day,” said Chalk. “In our particularly niche role, which is just trauma patients, it’s [more often] the young, and that has a huge emotional component to it. It’s important to be able to make sure people aren’t damaged by that.”

However, he said that most paramedics leave with the same unbridled enthusiasm for the role they had when they arrived. “It’s easy to forget that it’s often someone’s lifetime career ambition to get to this point, and then you realize how lucky you are to be here all the time.”

Continued Innovation

Reflecting on the service’s development, which has mirrored the development of the field of pre-hospital medicine, Davies said it has had to overcome many challenges — both at home and abroad. “The politics within London were intense to try and stop the helicopter in the first couple of years, and the North American literature was saying [prehospital medicine] is a waste of time, it just kills people,” he said.

“I was under no illusion at the beginning that it would be an easy path to tread; but in medicine, and probably life in general, anything that’s easy to do is probably not that worth doing — to do really meaningful stuff, you have to be prepared to take hits.”

And the team at London’s Air Ambulance certainly isn’t resting on its laurels, even after 25 years of continual innovation. Clinically, Davies said the service is on the verge of some major advances in terms of managing injured patients, such as super cooling them to a form of suspended animation. “There’s a group of patients that still don’t survive no matter what we do to them. We’re beginning to understand what’s happening to those patients, and it isn’t just mechanical — it’s much more molecular and biochemical. There are procedures that are going to roll out that will mean a lot of patients that currently die will live. And it’s not that far away.”