If you had turned on the radio in Nashville, Tenn., on July 5, 1984, you might have heard “Somebody’s Needin’ Somebody,” which was then enjoying a brief stint at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart. Written by Len Chera and performed by Conway Twitty, “Somebody’s Needin’ Somebody” is a song about loneliness and longing, but also hope: “Oh, there’s got to be somebody, out there waiting for me,” Twitty was crooning over the airwaves that summer, in a voice too deep and full to leave room for doubt.

In fact, there was somebody out there waiting for Twitty, or anyone else who might have needed help in the world’s country music capital that day. July 5, 1984, was the first day of operations for Vanderbilt LifeFlight, a new helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) program at Nashville’s premier teaching hospital, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The somebodies “waitin’ by the phone” — a pilot and two flight nurses — probably weren’t the soulmates that Twitty and his listeners had in mind, but they, too, had “much to give.” And they fulfilled that promise the very next day, when Vanderbilt LifeFlight performed its first ever patient transport.

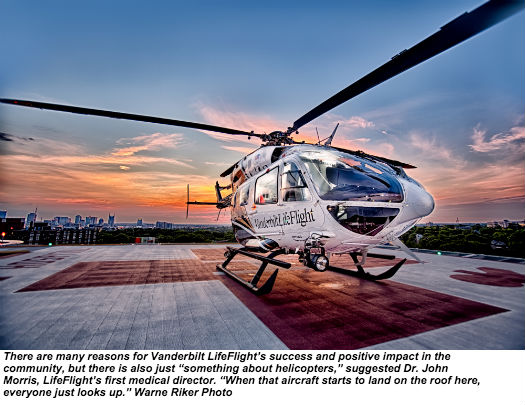

Thirty years later, the music has changed — Luke Bryan’s “Play It Again” was the No. 1 Hot Country Song for July 5, 2014 — but there’s still somebody in Nashville waiting by the phone, ready to respond to hurt and need. In its three decades of operation, Vanderbilt LifeFlight has performed more than 40,000 patient transports, becoming as essential to the fabric of Music City as Music Row itself. Last year, the program even made it into a country music video: Tim McGraw’s “Highway Don’t Care,” featuring Taylor Swift and Keith Urban.

Of course, the program itself has changed,

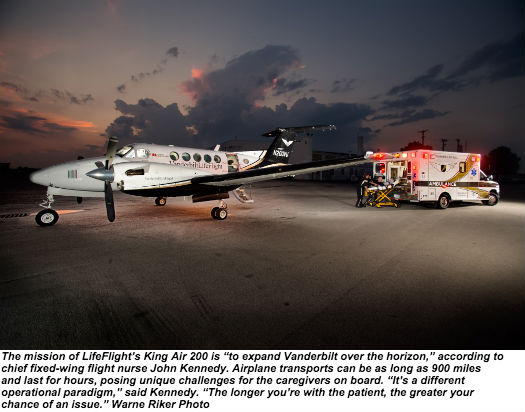

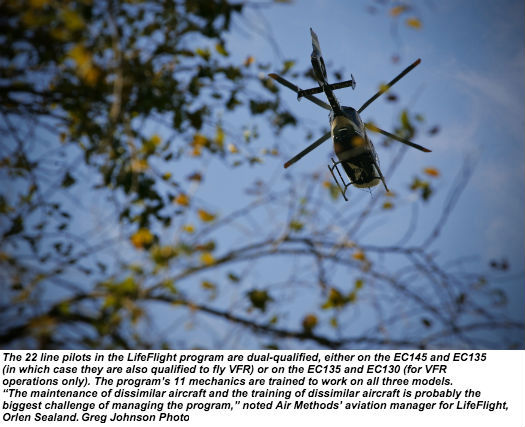

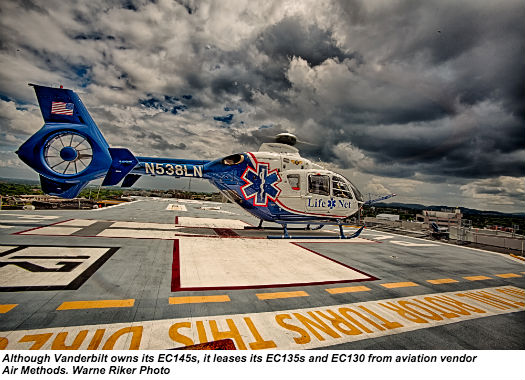

too. From humble beginnings and a single Bell LongRanger helicopter, Vanderbilt LifeFlight has grown into the expansive program it is today, with approximately 180 employees, five satellite bases, and seven aircraft: three Airbus Helicopters EC145s, two EC135s, one EC130, and a King Air B200 airplane. Throughout, LifeFlight’s relentless focus on safety and quality have made it a stellar performer in the HEMS industry; a top program from an aviation perspective as well as a clinical one. Country music stars may come and go, but for 1,560 consecutive weeks and counting, Vanderbilt LifeFlight hasn’t dropped off the charts.

Bringing Vanderbilt to the Patient

Vanderbilt LifeFlight was the inspiration of two Vanderbilt physicians, Dr. Joseph C. Ross and Dr. John L. Sawyers. In the early 1980s, their goal was to establish Vanderbilt University Medical Center as a leading regional trauma center — but trauma patients, of course, don’t always just walk in the door. Ross and Sawyers recognized that a helicopter air ambulance would be an ideal way to bring trauma patients to Vanderbilt, and in 1983, they received approval from the state to launch middle Tennessee’s first air medical transport service. Vanderbilt contracted with Kenn Air for a Bell 206L LongRanger helicopter, and brought on Dr. John Morris to serve as the program’s medical director.

Thirty years later, Morris recalls that, when he came to Vanderbilt, “I knew absolutely nothing about running a helicopter program.” As a first step, he made a pilgrimage to the HEMS pioneer James “Red” Duke, a trauma surgeon at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center who was instrumental in setting up Memorial Hermann’s Life Flight program in the 1970s. “We literally started with, ‘How do you get on the aircraft, and how do you get off?’” Morris said. Although the learning curve was steep, Morris and his colleagues embraced it, and LifeFlight was soon ready to commence operations with emergency department personnel who had volunteered for flight duty.

From the beginning, Morris saw LifeFlight as more than

just a way to bring patients to Vanderbilt — it was a way to bring Vanderbilt to those patients. “The concept was to push sophisticated resuscitation earlier and earlier into [the] patient’s course,” he said, recalling how, in the early years of the program, he would meet and debrief the flight nurses after every transport. That early focus on patient outcomes and clinical excellence was instrumental in shaping LifeFlight into what it

is now: a cutting-edge medical program with a mandate for continuous improvement.

LifeFlight was soon such a successful component of Vanderbilt’s trauma program that, in 1986, it was able to upgrade to a more capable, twin-engine MBB BK-117 helicopter. Over the next decade, LifeFlight’s volume grew steadily, and

in 1997 it expanded its operations by adding a second BK-117 along with additional personnel. The following year, LifeFlight upgraded one of its BK-117s to enable single-pilot instrument flight rules (IFR) operations, allowing it to safely accept some calls it previously would have turned down due to weather.

In 1998, LifeFlight completed 1,500 patient transports, and in 1999, it set a new record for the program with 1,659 patient transports.

For the first 15 years of its existence, LifeFlight thrived as

a relatively small, centralized organization. Its proximity to Vanderbilt University Medical Center allowed its flight nurses to make rounds with attending physicians, enhancing their professional development and allowing them to follow up with the patients they had transported. Soon after the program acquired its second aircraft, however, its managers had to acknowledge that this centralization — which was such a fantastic perk for clinicians — wasn’t necessarily optimal for patient transports. “It was rapidly recognized that we needed to position ourselves closer to the patients,” recalled current interim program director Lis Henley, a flight nurse who has been with Vanderbilt since 1998 and with LifeFlight since 2000.

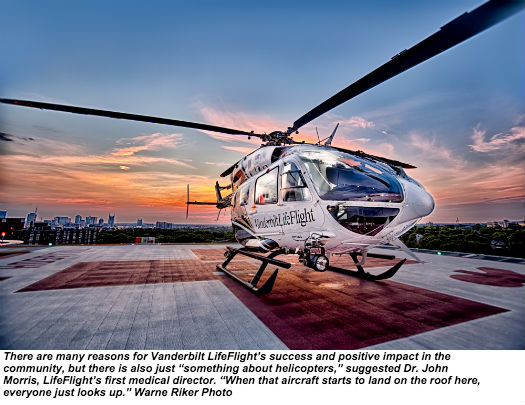

Thus began a period of expansion that ultimately resulted in LifeFlight’s current network: six helicopters at five satel- lite bases strategically positioned throughout Tennessee. The first satellite base to open was LifeFlight 2 at Bedford County General Hospital in Shelbyville (later relocated about 15 miles southeast to Tullahoma). In 2002, the LifeFlight 3 base opened in Clarksville; in 2004, LifeFlight 4 opened in Mt. Pleasant. The same year, LifeFlight 1 relocated from the Vanderbilt campus to the Lebanon Municipal Airport, 30 miles east of Nashville. LifeFlight opened its fifth base, in Smyrna, in 2011. Along the way, in 2003, it added fixed-wing service; its current King Air B200 airplane is based at the Nashville International Airport.

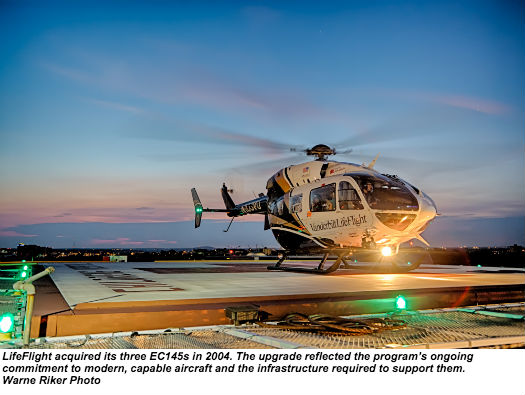

While LifeFlight was expanding geographically, it was also upgrading its equipment and capabilities with an

eye toward enhancing the safety of the program. A major milestone came in 2004, when LifeFlight took delivery of the three EC145 helicopters that are now the cornerstone of its operations (the EC145s are owned, while the EC135s and EC130 are leased from Air Methods Corp., which has been LifeFlight’s aviation vendor for the past 15 years).

In June 2009, LifeFlight added night vision goggles for its entire fleet; now, according to Air Methods program aviation manager Orlen Sealand, “We do not fly at night without the goggles on board.”

More recently, LifeFlight has taken the next step toward improving the safety of its flight operations by investing in a low-level IFR route structure throughout its service area.

Developed in conjunction with Hickok & Associates, the structure encompasses 16 instrument approaches connected by dedicated low-altitude IFR routes, which are validated annually. “It provides us safe separation with other IFR traffic,” explained Sealand, who said that, while only a small number of LifeFlight transports are conducted under IFR, “it’s a tool and a skill . . . that gives us a unique capability to respond.”

Safety and Quality

Vanderbilt LifeFlight’s commitment to the best tools for

the job — from modern, capable aircraft to a dedicated IFR route structure — is one of the ways in which it exemplifies a culture of safety. The program has pulled other best practices from the HEMS industry, too: it has a strong pilot training program, and protocols designed to minimize pressure on crews to accept flights. LifeFlight has a well-equipped, well- staffed communications division that acts as the local agent for Air Methods’ operational control center (its communications specialists undergo the necessary training to ensure compliance with Federal Aviation Administration requirements). Because LifeFlight’s bases are so dispersed, if one base turns down a flight due to weather, a communications specialist may offer it to another base, but will always state the reason for the turn-down. According to communications manager Jeff Gray, if a flight is not possible, LifeFlight also has the option of sending a critical care medical crew by ground ambulance — another way for patients to receive “the Vanderbilt level of care,” he said.

LifeFlight has been accident-free for its three decades of operation, and while the program’s employees are proud of this record, they’re not complacent about it (indeed, it seems impossible for any of them to mention it without knocking on wood). Early in its history, LifeFlight was deeply affected by a fatal accident at a neighboring program, which drove home the high-risk, high-stakes nature of helicopter EMS.

According to Dr. John Morris, a side effect of that accident was to ease competitive pressure on the program, giving LifeFlight’s employees “the ability to discipline ourselves.” Now, he suggested, the program’s safety culture is simply ingrained, despite a recent increase in competition from community-based HEMS programs.

If safety is LifeFlight’s highest value, however, quality is a close second. “My vision has always been that we are the safest program we can possibly be while delivering the highest level of patient care,” said Jeanne Yeatman, who spent 10 years as LifeFlight’s program director — and was a recipient of the Association of Air Medical Services’ Program Director of the Year Award — before being promoted to administrative director, Vanderbilt Emergency Services. LifeFlight’s standards for clinicians are high, and its expectations for professional development are higher; no one who joins the program is allowed to spend their career coasting on what they already know. Not surprisingly, LifeFlight tends to attract driven high performers who draw inspiration from their equally driven colleagues.

“Part of my inspiration primarily comes from the people I work with,” said flight nurse Tom Grubbs, who joined the program six months after it started and has now completed an incredible 5,300 patient transports. “Out of every single person we have here, every single one of them is better than anyone in the world at something. I’m in this chase to be as good as them.”

LifeFlight’s emphasis on continuous improvement is strongly influenced by Vanderbilt’s status as an academic medical center. Today, LifeFlight medical director and assistant professor of Emergency Medicine Dr. Jeremy Brywczynski carries on the tradition started by Dr. John Morris — the drive to innovate in ways that tangibly improve patient care. Brywczynski oversees continuing education for LifeFlight’s far-flung clinicians, a challenging task that has been aided in recent years by advances in web-conferencing. He also develops protocols for the implementation of new procedures and medical equipment, which continue to ramp up the sophistication of the care provided in flight.

As Brywczynski described it, the introduction of new technology and techniques into the aircraft “is not something you can do willy-nilly.” When Brywczynski is evaluating a new procedure or piece of equipment, he will start with a thorough literature review to explore it further. If the literature review is encouraging, then the procedure or equipment will be trialed with a select group of LifeFlight’s highest-performing and most experienced clinicians. Only if the trial supports

the innovation’s merit will it be introduced to the rest of the program through rigorous training. Even then, clinicians will retain the option of using the original procedure or piece of equipment until they’re completely comfortable with the new one. “I want to review and study things to make sure it’s truly safe, what we’re doing,” Brywczynski explained.

Beyond its in-house trials, LifeFlight’s affiliation with Vanderbilt provides it with an opportunity to participate in some large-scale trials, too. Currently, the program is taking part in the Department of Defense’s national, four-year Prehospital Air Medical Plasma (PAMPer) trial, which aims to determine whether administering plasma in flight can improve outcomes for critically injured patients with uncontrolled bleeding. Vanderbilt LifeFlight’s aircraft already carry blood on board; in the PAMPer trial, its Clarksville-based helicopter is carrying plasma on board for random month long intervals, and administering it to patients who may also receive blood. According to Dr. Richard Miller, Chief of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care at Vanderbilt, the trial “paves the way for advances in pre-hospital care that can ultimately save more lives.”

Community Outreach

Although LifeFlight’s branching into satellite bases has presented challenges for training and standardization, it

has done much to further another important aspect of the program’s identity — as a tool for extending Vanderbilt’s reach into the surrounding community. Here, the program’s impact has been profound. With more than 40,000 patients transported over a 30-year period, LifeFlight has touched a tremendous number of lives; if you live in middle Tennessee, you probably know someone who has benefited, directly or indirectly, from the program’s services. According to Lis Henley, it’s telling that “LifeFlight” is used as a verb as often as a noun: patients in the Nashville area aren’t “medevaced,” they’re “LifeFlighted.”

But LifeFlight’s reach into the local community extends well beyond patient transports. “It’s really important to be involved with your community,” Henley said, noting that, “To support and educate the community, we provide a lot more classes now.” Last year, through various education programs, LifeFlight trained more than 3,000 first responders in everything from pediatrics to critical care. LifeFlight personnel have also been heavily involved in developing standards for and training Tennessee’s critical care paramedics. There are now more than 300 paramedics in the state who hold the advanced certification (some of whom work for LifeFlight; in recent years, the program has shifted from a nurse-nurse to a nurse-paramedic medical crew member staffing model).

A particularly unique example of how LifeFlight serves the local community can be found in its event medicine division, which was founded in 2008 to provide EMS support to the Bridgestone Arena. Today, the division employs around 40 pro re nata (PRN) personnel who between them cover around 700 events per year — including the Country Music Awards and Nashville’s New Year’s Eve, two of the massive events for which the city is famous. According to event medicine manager Leigh Sims, the division provides a rapid response capability at venues that often need it, while also relieving pressure on local emergency agencies. “Vanderbilt is very serious about their outreach effort — taking that expertise and placing it out in the community where it can benefit people,” she said.

Besides being good for the community, such diversification is also smart business. Although Vanderbilt LifeFlight and Vanderbilt University Medical Center are nonprofit organizations, they’re not exempt from worrying about their bottom lines; finding new ways to capitalize on LifeFlight’s resources and expertise benefits everyone in the system. In that vein, LifeFlight’s fixed-wing crews began providing transport for Vanderbilt’s organ transplant teams in 2012; the program now conducts around 50 to 60 organ transplant flights per year. “That’s been a great combination of need and available resource,” observed John Kennedy, LifeFlight’s chief fixed- wing flight nurse.

More unusually, LifeFlight has leveraged the resources of its communications division to provide a number of services beyond simply dispatching flights. In 2009, the program established a discharge transport management office within its communications division to improve the flow of patients who require ambulance transport upon their discharge from Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The office now has three dedicated ambulances for transporting patients to their homes or other facilities, and also manages the contract ambulance providers who absorb the overflow. “We hold every ambulance to a performance standard, and follow

up when we need to,” said Elizabeth Worsham, LifeFlight’s supervisor for discharge transportation. She said the office has been successful in improving the efficiency of discharge transports, as well as the experience for both patients and case managers.

As healthcare reform changes the landscape of reimbursement for medical providers, innovations like these will only become more important. “It’s always going to be about efficiencies,” remarked interim program director Lis Henley. “How can we do things leaner and be more efficient?” Henley said that LifeFlight is currently focusing on ways to use data to drive efficiencies.

The program is also using data to validate patient out- comes, compiling evidence that can be used to demonstrate the difference in its high standard of care.

Customer service is another element of LifeFlight’s business strategy, and has been a particular focus for LifeFlight’s

communications division, according to communications manager Jim Gray. “Because we are the first contact and the impression of what Vanderbilt LifeFlight is, we really focus on customer service and professionalism,” he explained. One simple way in which LifeFlight has improved its customer service has been to keep its customers — the first responders who call for patient transports — on the phone while consulting with flight crews on weather and availability.

“If they hear us doing something, they know some- thing’s happening; it’s not just a black hole it goes into,” he said. “People have a choice, and we realize that. . . . We need to make that choice easier for them.”

In many ways, Gray is typical of the employees at LifeFlight; he’s passionate about the program and his role in making it work. “Everyone who succeeds in this role is very concerned with outcomes,” he remarked. “You have to know that what you’re doing makes a huge difference to the patient.” On every shift, Gray knows that somebody, somewhere, is needing somebody, just as somebody did in 1984. And because of it, he and his colleagues are sitting by the phone, ready and waiting to help.